Godspeed Bobby Whitlock (1948-2025)

Keyboardist and Duane Allman collaborator Bobby Whitlock died Sunday at 77. A native of Memphis, Whitlock played on some important moments in rock history.

He was a founding member of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, a truly groundbreaking musical outfit that never gained the renown they deserved.

Whitlock played on George Harrison’s epic three-record set: All Things Must Pass (1970)

He was most famous as keyboardist and songwriter on Layla.

Whitlock was a great storyteller, with endless quotes about Duane.

I’ve referenced Bobby more than a couple of times: my post about Layla—“When Duane Met God”1 and he’s quoted pretty extensively in “Duane brought out the best in him. He made him play”2—part of my Marginalia series.3

Whitlock was active on social media and was never shy in his critique of Duane, something multiple folks pointed out to me when I posted about his death earlier this week.

Here are some stories from Bobby’s book, Bobby Whitlock: A Rock ‘n’ Roll Autobiography (2011) along with my commentary.

Learning slide from Duane

I knew Duane from the Delaney and Bonnie days, so we spent some time together when he joined [Derek & the Dominos] in Miami. He and I were in his room and he was playing his Dobro….

I asked him, “How do you do that so effortlessly?”

He said, “You can do it Little Brother, just get a fishing pole and a bottle of Jack Black and an eight-ball and your Dobro and that slide I gave you and go down to the pond and do what I showed you. It’ll come to you, just be patient.”4

(“Well, I tried it and I gotta say it did not work!” He later joked.)

He had showed me how to tune to an open E and had given me some real cool advice about where to put my thumb on the back of the neck, keeping it there as an anchor or a home to come back to.

Then when you went to the second position it was the same thing, very good advice.

It just takes being born to do it and do it well. It is something that you can either do with style or you just end up making so much noise.

Duane could make it sing for you.

Duane also said that you don’t have to go all over the neck to stay in the game. He could play every song in one position without moving to the second or third position.

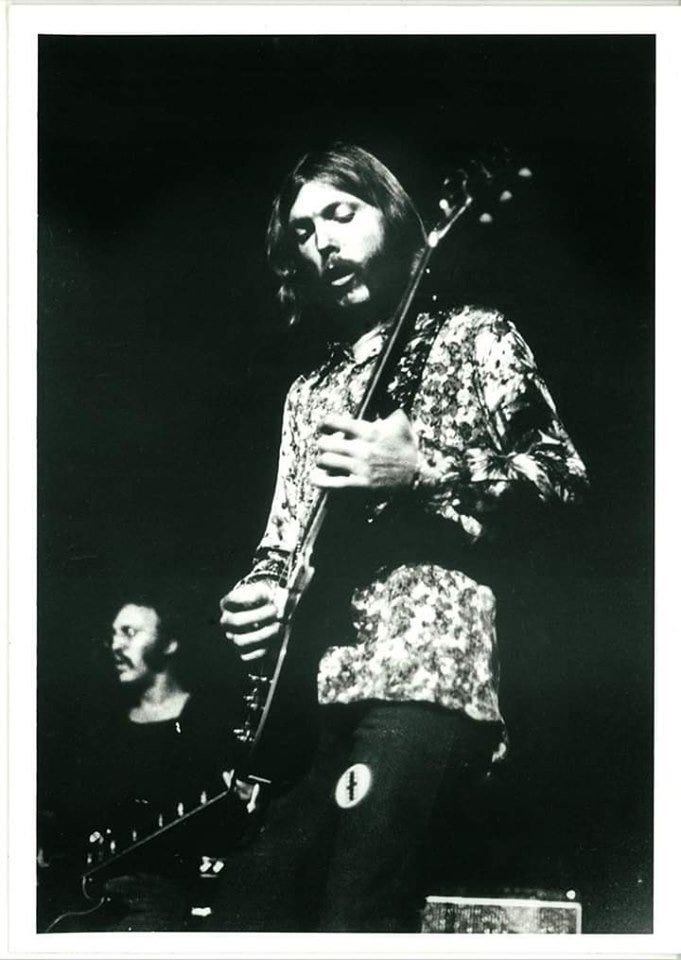

He was one of the very first to step up to the plate with an electric slide guitar and hit a grand slam every time he put that Gibson on and stuck that Coricidin bottle on his finger.

Some notes:

Duane had been playing slide for about two years and in open E for less than a year at this point. John Hammond, Jr. showed him the tuning when Duane played a session with him in Muscle Shoals in November 1969.

He wasn’t a natural, according to Johnny Sandlin. “He was in his apartment in L.A. with an old acoustic guitar. It didn’t sound very good at all back then when he first started. A lot of people don’t realize that before he learned to play slide, Duane was one of the top five players in the world. It seemed to me at the time that the slide was a detour in his playing. I’m not really proud of that lack of vision.”

This story is one of the rare times I’ve seen Duane quoted about his guitar technique. Take notes, folks.

Recording Layla

Whitlock’s book has a detailed song-by-song account of the Layla sessions. Here’s one example that stands out to me:

“Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” Sam “the Sham” Samudio suggested [it]. It seemed a good idea and went right along with the theme of the record, even though at that time we weren’t thinking about a theme.

This was Duane Allman’s first song with us. I believe that it was a song that he and Eric both had in common. Eric could really relate to it because he had lived that song and was to live it time and time again. Duane could relate to it because of where he came from and his musical heritage.

This song was recorded live, vocals and all, with no overdubs. It was the first take, but of course it was all worked out before we went into it.

This was a getting-to-know-each-other song.

Layla leaves an important circle unbroken: Southern music (Duane) and the British Invasion (Clapton), this time with the blues standard that Bessie Smith made famous in 1929.

And as Whitlock notes, Duane had indeed recorded it—September 1968, with the 31st of February, his pre-Allman Brothers’ collaboration with drummer Butch Trucks’s band.5

Clapton may have learned it from Steve Winwood, who recorded it with the Spencer Davis Group in 1966.

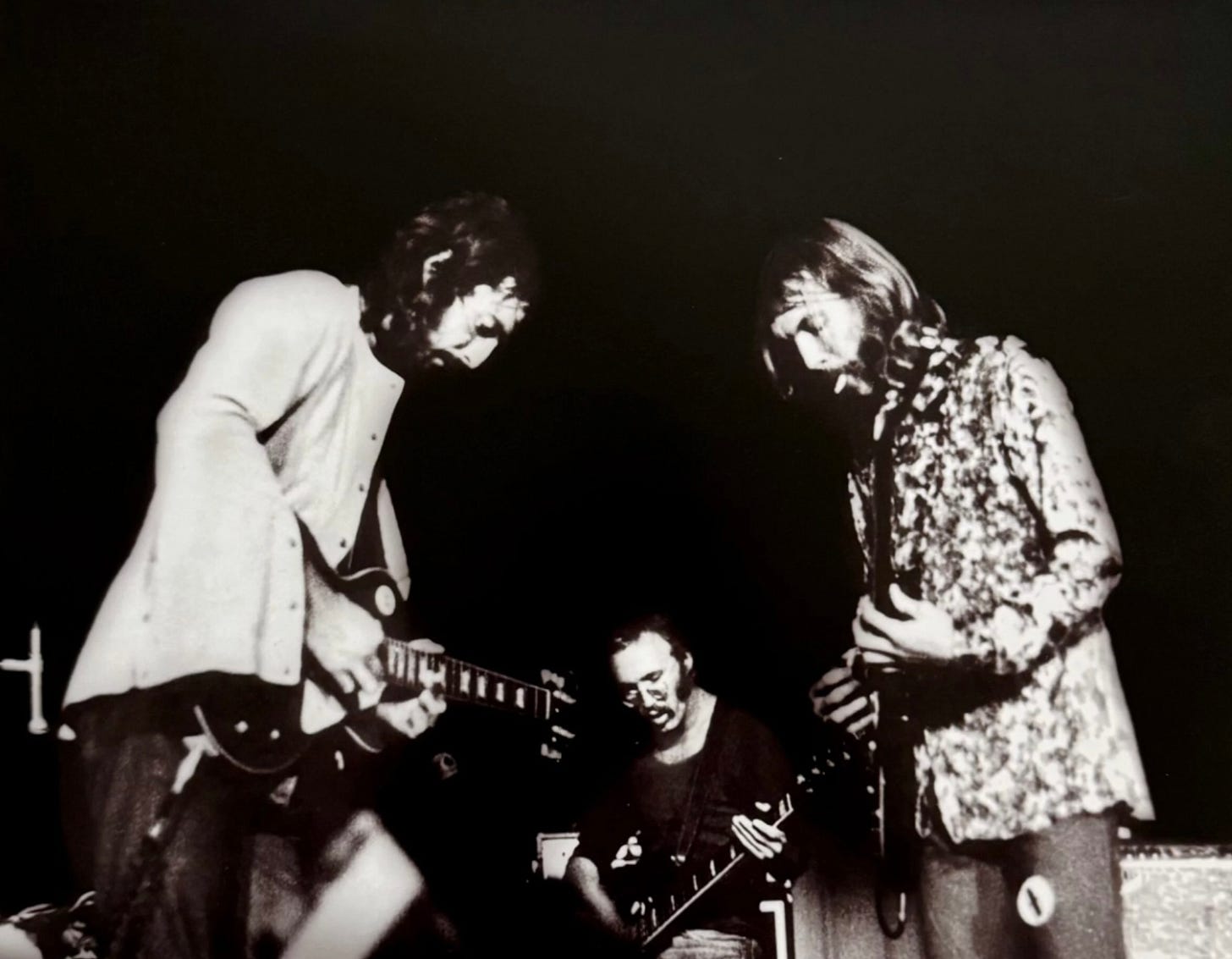

Duane was set up to the left of Eric and they would face each other while they played. And they looked each other right in the eyes.

This is a really cool detail. Looking directly at each other is also how Duane & Dickey often played.

Eric is playing through his Champ amp. Duane is on a Fender Twin that was set back a ways on the right.

Both Duane and Eric were very good leaders and made it easy to follow everything that was going down. Duane would let you know when it was coming and so would Eric.

As a band that was full-tilt improvisation at all times, physical cues were the norm for the Allman Brothers Band.

Playing live with Duane

Whitlock was less-enthusiastic about Skydog’s live playing after revisiting a bootleg of the first of two shows Duane played with Derek & the Dominos, 12/1/70 Curtis Hixon Hall, Tampa. (A rough recording exists.)

He started off speaking positively about the “Layla” opener, which, indeed, is really good.

They traded off being the support guitar when the other would go off. Eric was playing the rhythm while Duane played the lead and then they would switch roles. Eric was very gracious when it came to letting the other guy have his lead.

Our vocals worked great as usual, and the whole band was really excited on that night. A big part of that was because Duane was with us and we felt complete.

That was the balancing factor with our record, a combination of Duane and Eric’s unique styles with a combination that was respectful and worked as

“Duane was with us and we felt complete” is a pretty powerful line.

But then he followed it with these gems:

The second song was “Got to Get Better in a Little While,” a favorite of the band’s, but Duane's playing was not very creative, just big chords and rhythm.

The third song was “Key to the Highway” and is a real good example of what I’m talking about in relation to Duane being a structured player. The song sounds nothing like what we had recorded a few months before at Criteria. Duane played a pattern that Carl then Jim had to lock into. Eric and I were the only ones who were anywhere near the song and its essence. Duane was just not as fluid a player as Eric, so the songs and his part in them became a bit repetitious.

The last song was “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad,” and we rocked. Duane and Eric were trading off towards the end but there was no way that Duane could keep up with Eric.

The bootleg is a rough quality recording and there are times the band wasn’t completely in sync, but I don’t hear in Duane’s playing what Whitlock describes.

And I admit I’m biased, but I’ve genuinely never heard Duane out of his league on any recording, ever. I’ve never heard anyone else say it either.

As a whole Duane was not used to being around such players as Eric and Jim Gordon and Carl Radle…. Duane was great for our record but he would have not been good for our band in the long run because of his approach to what a band should be.

I think Duane understood after the Layla sessions that his Allman Brothers bandmates were every bit as talented as Clapton, Gordon, & Radle. It’s why he turned Clapton down for a slot in the band.

The Allman Brothers Band was his thing. He was fully confident in the players he’d assembled

Duane’s instincts paid off. Less than a year later, his band was riding the success of biggest hit of their career to date: At Fillmore East.

The Layla record was structured. Each song was gone through and worked out so we were sure. Even though it was live when we recorded it, we didn’t just walk in and start playing and that was all there was to it. It wasn't that way at all. “Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out” was a song that the Hour Glass did and Duane played the same licks on Layla record as he did with them.

Eric was and is a fluid player. Duane couldn’t keep up no matter how he tried. He was from a structured situation and was not used to creative flow and formless freedom.

Live he was not the guitar player for our band. We were not a southern rock band. We were a very sophisticated rock ‘n’ roll band with a lot more going on than playing the same old lick over and over in different keys.

Whitlock is the only person who I’ve ever seen disparage Duane’s ability to improvise, which was a hallmark of Duane’s going back to his session work in Muscle Shoals.

I’d argue that Layla is way more structured than the Allman Brothers’ music, which has room built in for improvisational excursions. Layla had jams, but all within pretty traditional song forms.

Ultimately, Whitlock had fond feelings for Duane

I remember when he came out and played with us live for a few shows on our U.S. tour and how full and complete the sound was. Then, when he left, how that completeness went with him. Because the album had two guitarists, when performed live there was a void that we tried to fill and it didn’t always work.

I believe that if Duane had continued with us, we would have had more structure and longevity. He was a born leader. He had a command of his ability to lead so the respect for him was an added thing that came naturally.

These paragraphs are interesting in light of Whitlock’s take on Duane’s live appearance with Derek & the Dominos.

I think they speak to his enduring affection for his time together with Duane.

They made some great music with Delaney & Bonnie even before Duane joined forces with Derek & the Dominos. And Layla is an all-time classic.

I loved Duane, he meant well. He surely was here to give, and when he did, he gave it his all. I’m proud to have been his friend and to have been affectionately known to him as Little Brother.

Duane and Bobby’s collaborations lasted only one year: 1970, but they were damn sure significant.

PLAYLIST

This Youtube playlist includes tracks I mention here, the full 12/1/70 Derek & the Dominos show, and two outtake jams from the Layla sessions, one with the Allman Brothers Band minus Jaimoe.

Lagniappes

Bobby released two solo albums on Capricorn Records: One of a Kind (1975) and Rock Your Sox Off (1976). The latter contains a cover of Layla’s “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?”

My good friend Alan Paul’s tribute is well worth the read: “RIP Bobby Whitlock, who never stopped hating the Layla coda!”

The “Layla” coda was a Rita Coolidge composition, “Time.” Jim Gordon, her once-boyfriend, failed to credit her for the song, an error that’s never been rectified.

In 1973, Rita’s sister Priscilla recorded “Time” with her husband Booker T. Jones.6

Thank you for supporting Conversation from the Crossroads.

I am grateful.

Randy Poe, Skydog (2006), 165.

Of Booker T. & the MGs, the Stax house band. Stax is also where Whitlock got his start.

Thanks for this excellent tribute for a great musician, Bobby Whitlock. He will be missed. I'm going to see TTB in September. What I love about them is how the evolution of their music comes from Delaney and Bonnie, Derek & the Dominoes, the Mussel Shoals sound, The ABB...

Thanks for all that. I like reading different perspectives & opinions even when they're not positive, and then I like to hear responses by people who are equally knowledgeable.