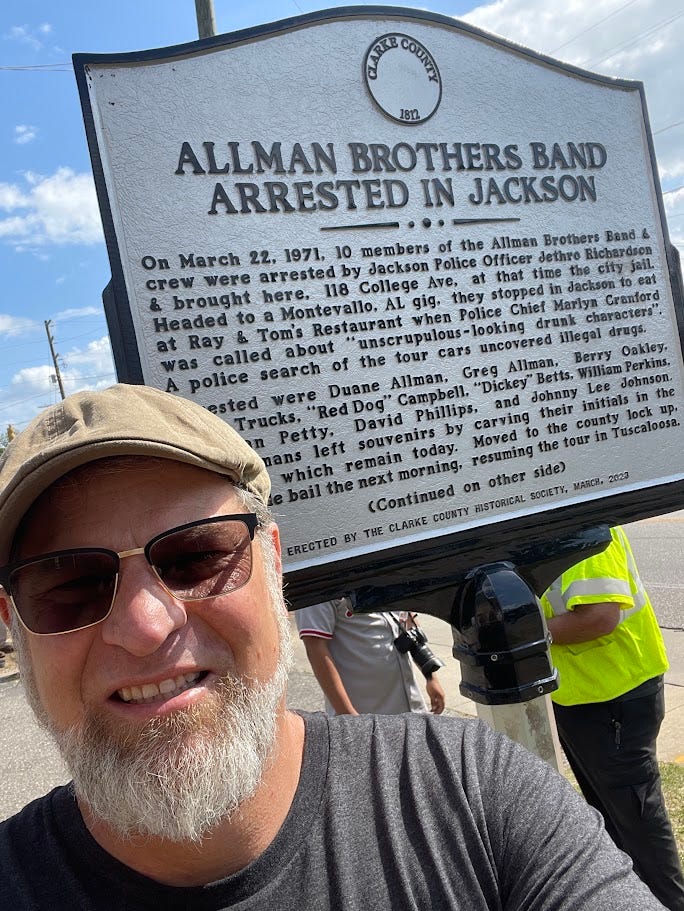

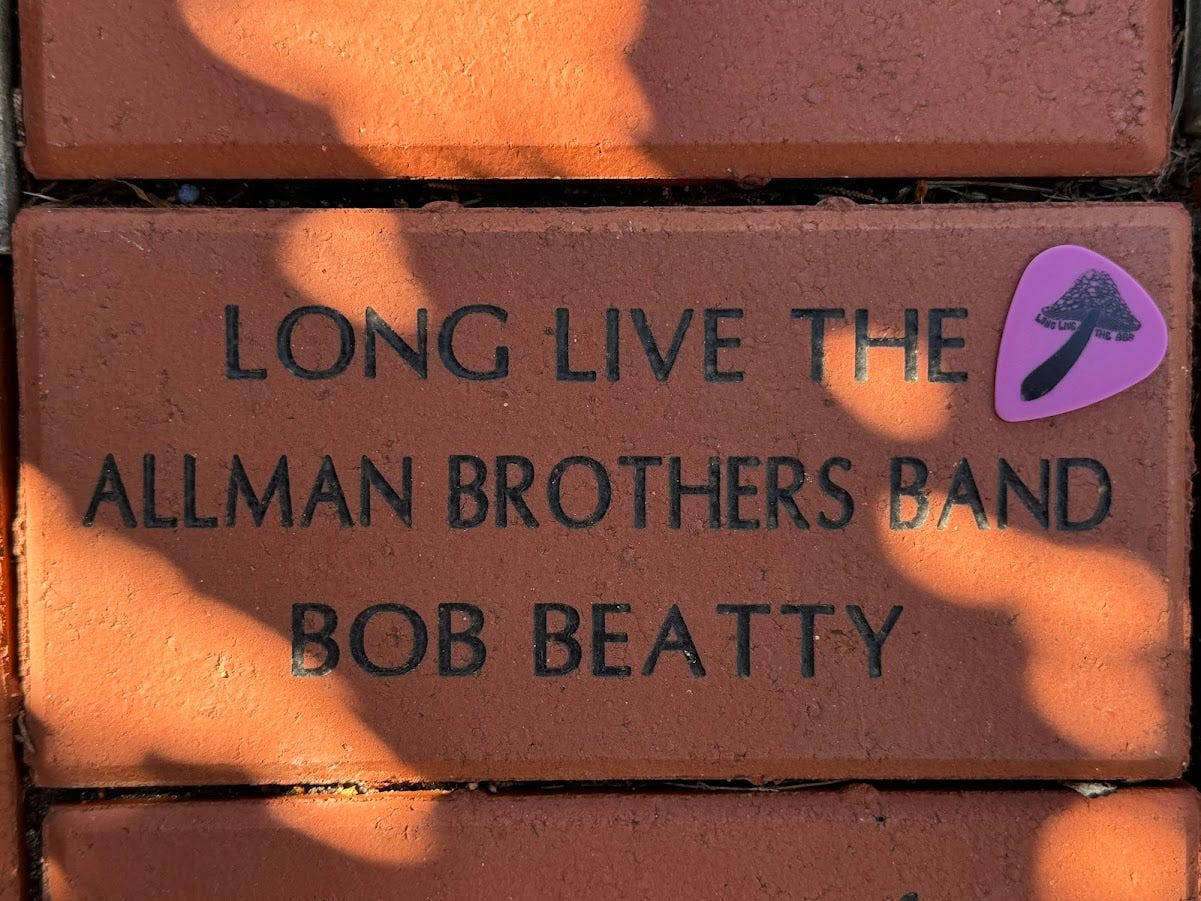

In April 2024, the Clarke County Historical Museum in Jackson, Alabama, invited me to speak at a historical marker dedication for the Allman Brothers Band’s March 1971 arrest in Jackson, Alabama.

Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East1 is as much a local history as anything. I did my best to frame the conversation around the local connections. Not just the arrest, itself, but the ways the Allman Brothers Band’s story is a story of the small-town South. This relates to my own work in state and local history over parts of the last four(!!!) decades.

With Play All Night, I did my best to tell a story that was interesting not only to fans and fellow hardcores, but to general readers. History is all about contingency; it’s about “if, then.” History is also less useful without context. It is the story of their lives in a particular time and place: the small-town South of the 1960s and 70s. One of my goals was to place the Allman Brothers Band’s story in situ.

This video is that talk verbatim. What followed was a tour of the jail, which is now Bigbee Coffee Roasters.2

Below is a transcript, cleaned-up for print for paid readers of Long Live the ABB

September 1968

Duane returns to the South for good. He is 21 and has just left Los Angeles in a fit of pique, quitting Hour Glass, his band with his brother Gregg, and fellow southerners Johnny Sandlin, Peter Carr, and Paul Hornsby.

He returns to his hometown of Daytona Beach, Florida. Soon, he and Gregg sign on with the 31st of February, their friend and fellow Floridian Butch Trucks’s band. They play some gigs together and join on demos for the group’s second album. Duane is furious when Gregg abandons ship for L.A. to fulfill Hour Glass’ recording contract.

October 1968

In October, Duane makes his way to Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Duane’s first session is with Clarence Carter.

In November, he plays on “Hey Jude” with Wilson Pickett. And that’s really where everything in the story comes together for Duane.

(I’m leaving a lot out. I’ve written an entire book that covers all of this. You should buy it if you don’t already have a copy 🍄)

November 1968: “Hey Jude”

Anybody who was alive and was of radio listening age would’ve heard Wilson Pickett’s “Hey Jude” all over the radio in spring of 1969. With this incendiary guitar solo at the end, Duane Allman going toe-to-toe with “Wicked” Pickett.

From that guitar solo, Duane Allman earns a contract with Rick Hall of FAME Studios in January 1969. By February, Phil Walden, manager of the late Otis Redding, buys out Duane’s contract.

Duane doesn’t write. He doesn’t sing. He doesn’t even have a band. But “Hey Jude” gave him the chance to create a band his own way. After four years of intense grinding, Duane’s efforts begin to pay off.

Enter Jaimoe

The first guy to show up is Jai Johanny Johanson, Jaimoe. An African American drummer from the r&b circuit, Jaimoe was also a jazzhead. Duane’s band was already going to be playing Black music, a Black member adds authenticity in music and spirit.

In February 1969, Jaimoe moves in with Duane in Muscle Shoals, in a cabin on Lake Wilson. They begin playing together in Muscle Shoals and are soon joined by bass player Berry Oakley, who’s in a band called the Second Coming out of Jacksonville.

Duane has been courting Berry for about 6 months. They met after an Hour Glass show in Jacksonville in 1968. Berry’s band includes Dickey Betts, a hotshot guitarist whom Berry adores and is reluctant to leave behind.

Duane’s already a hotshot guitarist, but he hears potential when he and Dickey play together.

By March, Duane and Jaimoe relocate to Jacksonville, where the band grows to include a second drummer: old pal Butch Trucks.

After several weeks jamming, Duane calls Gregg, who’s still in Los Angeles and says, “We got it shaking down here and all we need is you. The cats love to play. They’re all really into their instruments, they sing a little bit but there’s not a whole lot of writing going on so I need you to come and sing and write and round it all up and send it in some sort of direction.” It was, Gregg said, “The finest compliment I ever had.”

March 1968: Jacksonville

Duane and Gregg were estranged when Duane put the band together. They had not been on speaking terms for about six months because Gregg quit the 31st of February and hightailed it back to L.A., where Liberty Records was going promote him as a star.

Duane was pretty mad at him. But, as he told Jaimoe, “I can’t think of another motherfucker who can sing in this band except my brother. That’s who I really want.”

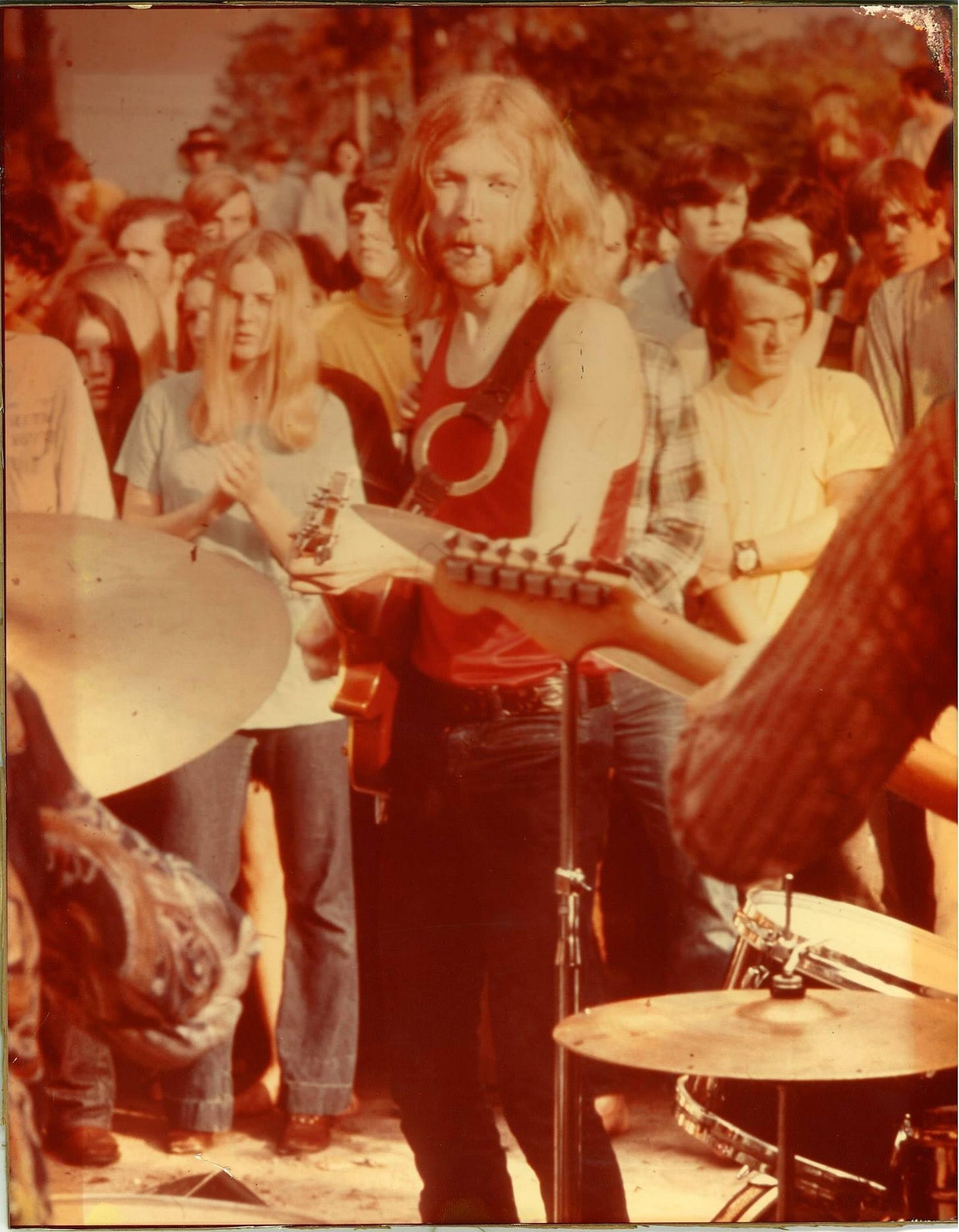

Gregg shows up to Jacksonville on March 26, 1969. Duane, Jaimoe, Berry, Dickey, and Butch are playing “Trouble No More.”

Gregg walks in, backs up against the wall with his hands up and says, “Jesus Christ, what a band!”

He pulls Duane aside and says, “I’m not sure I can cut this.”

Duane replies something to the effect of, “You little punk… How dare you? I got all these nice people here telling ‘em how great you are, and now you’re too afraid to sing.”

“Count the damn thing off!” Gregg answers. And so begins the 45-year career of the Allman Brothers Band.

Gregg joins a band with diverse musical backgrounds. Its emphasis is on southern music—ranging from rhythm and blues, blues, rock & roll, country, jazz, psychedelic music, etc. It’s a melting pot of talents and traditions.

A story of resilience

The original band stays together for a little over two years of backbreaking touring. In October 1971, right as the album At Fillmore East is breaking out, Duane dies in a motorcycle accident. One year and thirteen days later, Berry Oakley dies similarly right around the corner from where Duane was killed.

In each case, the band continued on.

That fact is why we’re here and why we continue to be here.

Yes, it’s the music they put out, but also that they continue on in the face of adversity. It’s a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame band, they’ve sold millions of albums. They stay together (more or less) for 45 years and survived a bitter divorce with Dickey Betts in 2000.

“Southern change gonna come at last.”

They are one of the most significant bands of their era and of their generation. They led the Southern counterculture and offered a voice for Southern youth.

They answered Neil Young’s call in “Southern Man” in the music that they played, the company they kept, and their fierce commitment to inclusion. They created their own legacy for Southern music and led the way for the Southern rock genre.

And the story could have only happened in the American South.

L.A. has a pretty tight musical production method. That included pretty odious contract terms for up-and-coming musicians. In Duane and Gregg’s case, Liberty Records renamed them Hour Glass and dressed them up in psychedelic finery. It was a gimmick, and out of character for Duane.

Liberty and producer Dallas Smith had had success with teen idol Bobby Vee, and it’s pretty apparent he had similar designs for Gregg. “Oh, this, this dude’s good looking and he’s got pipes and he’s got this blonde hair and he’s got all this charisma.” They were trying to make him the front man, and that frustrated Duane, who was the bandleader and a great guitarist.

In April 1968, Hour Glass goes to Muscle Shoals and record demos for their second album. FAME is an independent studio, and they do things differently than in L.A. They’re having a good time recording because in the South things are a little looser. Hour Glass records these demos and they love them. Liberty Records rejected them altogether.

The South, is a big, BIG part of this story. Five of the original Allman Brothers are southerners. (Berry Oakley’s actually from Chicago, but moved “down South as soon as I had enough sense.”)

They’re Southerners who feel a deep sense of place. It’s where they have a certain comfort level.

And they failed each time they left the South. And when Hour Glass breaks up, Duane determines to do it his way. He finds musicians who support his vision. And with Phil Walden as manager, they were able to grow their music and their sound without the pressure of having to record AM radio hits.

Duane’s career lasts about four years: 1967-1971. It’s a really short, meteoric career. And the South was pivotal to it. When he comes back home for good in 1968, that’s when he makes the music that he’s most famous for.

Muscle Shoals is where Duane grounded himself. “I got a little cabin on a lake by myself,” he said, “and just sat there and played, getting used to living without a bunch of jive Hollywood crap in my head.”3

Touring in the 70s

Touring was an intense experience. The Allman Brothers Band represented the counterculture, and touring as hippies offered complications. “It was a different world,” Bruce Hampton recalled. “It was life or death. You’d stop at a gas station and you’d wonder if you were going to die. That’s no joke. If you had long hair, you were a target.”

Gregg described “perennial redneck questions: ‘Who them hippie boys and who’s the n——r in the band?’ We dealt with that second question quite a bit. Keep in mind, this was the 1960s, we were in the deep South, so having a Black guy in the group came up a lot. But Jaimoe was one of us and we weren’t going to change that for nobody.”

In April 1970, road manager Twiggs Lyndon was arrested for the murder of a Buffalo club owner for not paying the band. Lyndon is found not guilty by reason of insanity; being on the road with the Allman Brothers literally cooked his brain. He served a year in a mental hospital/correctional institution.

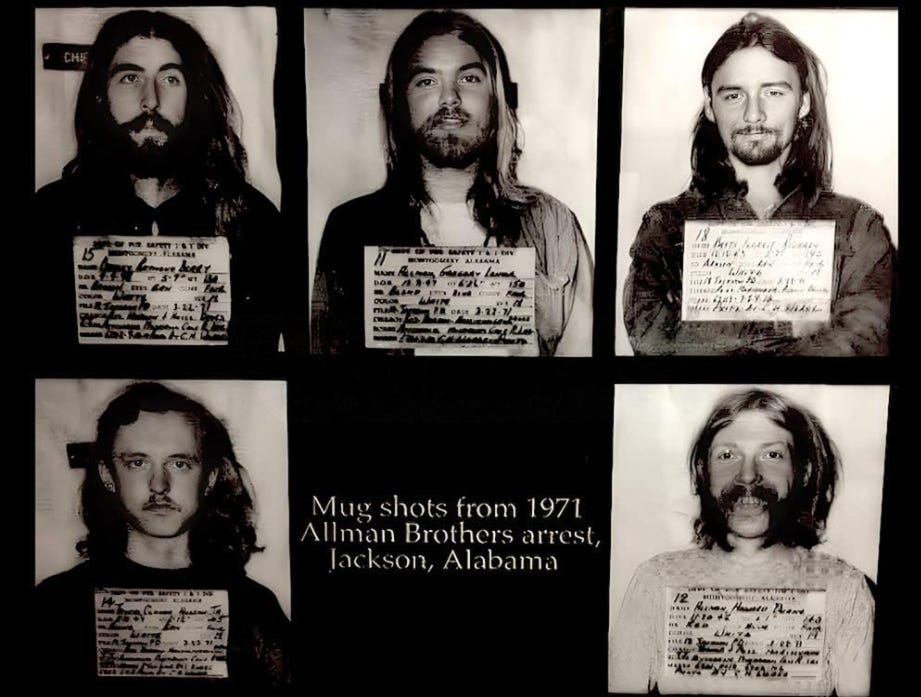

The band’s arrest in Jackson happens March 22, 1971, 9 days after the band finishes sessions for their landmark third album, At Fillmore East.

I can only imagine how fearful Jaimoe was when the band was arrested. “That Black guy is scared to death,” Sheriff Rip Armistead told District Attorney Hardie Kimbrough. In response, they moved the white members of the band into Black section of the jail with Jaimoe.4

The authorities were concerned for the band’s safety.

The Allman Brothers were complete unknowns, but they looked like shit, were carrying a ton of drugs, and might inspire some sort of youth rebellion if word got out they were in the local pokey.

Jaimoe was right to be scared, but the powers that be were doing all they could to get them out of town as quickly as possible. As one of the local judges told me, “We weren’t much worried about drugs. It was bootlegging we were concerned with.”

The case was resolved March 6, 1972. The charges were reduced from drug possession to disturbing the peace. The band members forfeited their bonds and bypassed Clarke County from that point forward.

Gregg and Berry both referenced the case as they introduced “Hot ‘Lanta” on February 10, 1972 in Macon. Gregg dedicated the song to “the people in Jackson, Alabama—you know who you are” with Berry sarcastically adding, “Why we met some of the nicest folks down there!”

In 2016, the Clarke County Historical Society published a piece on the arrest from the point of view of the Jackson authorities: “Famous Band Arrested in Jackson, Spent the Night in the Clarke County Jail in 1971” jibes (more or less) with ABB road manager Willie Perkins’s accounts in his books No Saints, No Saviors (2005) and Diary of a Rock and Roll Tour Manager (2022).

The arrest in context

The Allman Brothers were arrested the morning of March 22, 1971. They had just played a show at the Warehouse in New Orleans and were headed to a gig at the University of Montevallo that night.

It was nine days after the Allman Brothers finished recording At Fillmore East, the groundbreaking live album they released after their two studio records hadn’t broken through. The band recorded their third album in their natural element: Live. It was a different approach to what Duane had to follow in New York, Nashville, and Los Angeles.

More than 50 years later, the album continues to resonate as a clear documentation of Duane and his band’s artistic vision.

It is a large band composing in the moment.

Communicating musically, improvising.

Listen to At Fillmore East closely. There’s not a single overdub. None. Zero. They patched two versions of “You Don’t Love Me” together, and they took out Thom Doucette’s harmonica solo in “Stormy Monday.”5

It is 78 minutes of beautiful music.

I love how each musician integrates himself into the whole, how soloists conjure riffs on the fly, and how the band plays behind the soloists—pushing and prodding them forward, backwards, even sideways.

At times the guitars stand out; other times it’s the drums. Sometimes it’s Gregg’s vocals or the magnificent, swirling sound of his Hammond B-3. Undergirding it all is a rock-solid foundation of ensemble playing, each musician making up his part as he goes along.

It is a musical conversation.

And the Allman Brothers Band are among the premier musical conversationalists in the history of rock.

To this day after hundreds (thousands?) of listens, I’m still hearing new things.

At Fillmore East endures because it’s a well-conceived, brilliantly recorded album.

Producer Tom Dowd captured that room beautifully. You can hear the collective exhale at the end of “Hot ‘Lanta” and an audience member yell out “Play all night!” in the quiet moments of “You Don’t Love Me.”

And don’t forget: this is New York City, which has a continual murmur to it. You ever been to New York? There’s a lot of energy in New York City and rooms like Fillmore East are popping.

And when the band is playing, that crowd is on edge. When the band is quiet, the crowd is whisper-quiet. They’re listening intently.

And it worked.

The band wanted to put a record out that sounded like them on stage. That’s what they were best known for, live performance. Live, Duane and bandmates expressed themselves most freely.

Capricorn Records created a campaign to take advantage of the Allman Brothers’ reputation among the rock underground. “This is the People’s Band,” Phil Walden said. “Music is for the people and therefore we want to make this specially priced”—a double album for a single album price.

Record buyers agreed. At Fillmore East was a remarkable commercial breakthrough for a band without a hit single, much less an integrated band of southerners with a predilection for jamming.

The week before release of At Fillmore East, the Allman Brothers Band closed Bill Graham’s Fillmore East. It was their only time headlining at the venue whose name graces their most famous album.

They still hadn’t had a hit record yet. They were on the cusp. People knew them, people expected a great record from them.

“The word had got out,” booking agent Jonny Podell said. “The tastemakers—Bill Graham and Rolling Stone—had come out forcefully in favor of the Allman Brothers. The network of underground clubs, from Boston Tea Party to the Fillmore West, clearly supported the Allman Brothers, and would play them five times a year if they could.”

The record was released July 6, 1971. Six weeks later, Duane Allman is dead.

It’s a beautiful, brilliant record. It’s timeless.

The record’s success is the pinnacle of Duane Allman’s musical journey but marks only the beginning of his enduring influence.

At Fillmore East birthed an explosion in southern music, with Duane’s surviving bandmates at the forefront of the “Southern rock” genre.

Random notes: Alabama and the Allman Brothers Band

Jaimoe is from Gulfport, Mississippi, and would often play clubs all along the Gulf Coast. The Almond Joys did as well. Duane first made his name at FAME in Muscle Shoals.

Chuck Leavell the piano player who replaced Duane in 1972, hails from Tuscaloosa. Paul Hornsby, of Hour Glass, is from that area as well. Hornsby became a big time producer for Capricorn. Johnny Sandlin, Hour Glass bandmate and producer of several Allman Brothers’ albums, is from Decatur.

Some more obscure connections:

Dickey named “Ramblin’ Man,” his most famous song, after Montgomery native Hank Williams’s song of the same name. That’s their one big hit, “Ramblin’ Man” hit #2 in 1973.

Cher’s “Half Breed”—recorded at Muscle Shoals Sound—kept them from the top spot. Two years later, Gregg and Cher marry.

Thanks for being here.

Give that Amazon algorithm a tickle please (Play All Night on Amazon); then click again and support independent bookstores here:

Reminder that this is 1971, seventeen years after Brown v. Board struck down segregation and seven years after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Doucette was the unofficial seventh member of the ABB.