You think we got a band now, wait ‘til my little brother gets here

Gregg arrives in Jacksonville

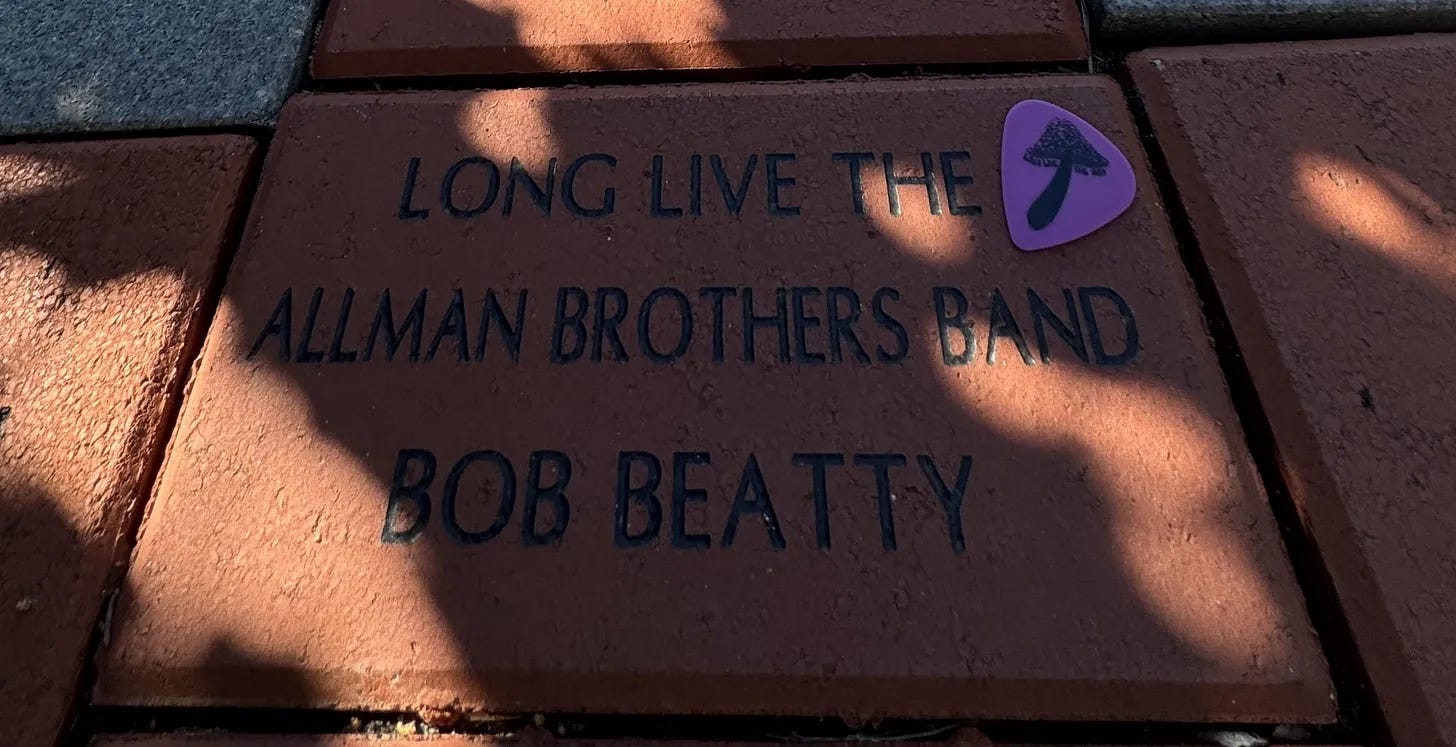

Welcome back to Long Live the ABB: Conversation from the Crossroads of Southern music, history, and culture.

My last post was part 2 of my deep dive into Dickey Betts as a composer of instrumentals. Dig it here if you missed it:

This is Part 6 of my annotated read of the Allman Brothers Band: A Biography.

Here’s the rest of the series.

This is the page I’m commenting on today1

It’s only seven paragraphs beginning midway through the first column and continuing midway down the second one.

Dr. B’s Marginalia

The original text looks like this.

My comments look like this.

Previously on Long Live the ABB…

“I don’t want no trio, I want six guys”

Duane has made the decision that his band would be him, Jaimoe, Berry, Dickey, Butch, and Gregg (still in California).

And he said, “I don’t want no trio; I want you, and I want Butch, and I want six guys!”

So we got six guys, because when we played, we made white people do things they hadn’t done in thousands of years. Stomp their bare feet on the ground, and dance. And they dug it.”

I ABBsolutely LOVE Dickey’s tongue-in-cheek description about the undeniable GROOVE of the Allman Brothers Band.

The remaining member of the Allman Brothers Band was still lingering in Los Angeles, writing songs as therapy for an unhappy love affair and feeling very lonely.

It’s a quirk of history that the last person to officially join the Allman Brothers Band in March 1969 was Gregg. The brothers had been estranged since the previous September, when Gregg fled Florida for California to fulfill Hour Glass’s contract.

Here’s where the book picks back up.

Duane broke the ice.

Gregg Allman: “Just as I was about to put the gun to my head, the phone rang. It was a Sunday morning, the first Sunday before March twenty-third, 1969, which was the date I got to Jacksonville.

Let’s stop and pause at how casually Gregg talks about depression here. This was the one time in Gregg’s life he and Duane were estranged and he was suicidal.2 Want proof? He had just penned two songs dripping with existential crisis: “Dreams” and “It’s Not My Cross to Bear.” (More on this later.)

And some nerdy stuff only I think about. Here’s one place where the earliest story conflicts with what became official. Gregg claims Duane called Sunday March 16, meaning it took him a week to get to Jacksonville. All his other accounts said he arrived in a matter of days. That’s why we celebrate March 23 as Jacksonville Jam Day (no Gregg) and 3/26/69 as the ABB’s anniversary (the day Gregg arrived).3

It was my brother. He said he had felt like a robot doing session work in Muscle Shoals, and that he’d decided to get a band together, to do some more traveling and playing around.

This is one of my favorite parts of Duane’s story. In Muscle Shoals, he finally broke through and got someone to recognize his talent. He signed a contract for a solo project and ditched it posthaste.

He missed gigging.

The months Duane spent in the Shoals were the only time in his adult life he didn’t spend regularly performing. “I wanted to get to playing in joints again, which is what I did before I did anything else. Play for people,” he said.

As I say here, it took some convincing for Duane to make the call.4

Marginalia reserved for paid subscribers of Long Live ABB

“Those cats in Muscle Shoals couldn’t understand why I didn’t just lay back on my ass and collect five bills a week,” he said. “I’m just not the laying-back-on-your-ass sort of person.”5

“I love working in the studio, and it is a very valuable experience,” he wrote to Donna Roosman, “but I know I was born to play for a crowd, and I’m really itching to get started.”6

Jaimoe and Duane left Muscle Shoals for Jacksonville to recruit Berry. Said Duane, “I told Rick [Hall] the studio thing was stringing me out and I wanted to go back to Florida and work in a little more creative capacity.”

“I’m just gonna ride around to various southern cities and just sort of sit in with the music scene and see what’s going on,” he told Phil Walden. “See if I can put together something that I have in my head.”7

The South was home, where Duane felt most comfortable. He knew he’d find musicians who shared his roots and spirit.

Gregg continued:

Duane said, ‘Man, I’ve got these five dudes that play just as purty as you please. I’ve got a dynamite lead player named Dickie8 Betts.’

‘Lead player,’ I said, what the hell you need a lead player for?’

‘Well,’ he says, ‘bay bruh’ - that’s what he called me, that’s a Black Southern term short for ‘baby brother’ - ‘We goin’ have two lead players. And I got two drummers.’

Duane and Gregg hadn’t spoken in six months, since Gregg left Florida for L.A. just as they were getting rolling with the 31st of February. In that time period, Duane had completely reimagined the band lineup he and Gregg had used since Daytona Beach.

Two lead guitarists??? Two drummers???

I thought that was the most ridiculous thing I’d ever heard. I said, ‘Oh you mean one’s playing congas.’

He says, ‘No, we got two full sets of traps.’

The band needed two drummers, Duane later said, “because we knew we was going to be playing loud, and both cats can play everything they need to play if there’s two of them instead of one cat having to flog his ass off the whole night.”

“Wait, what do you do?” Gregg asked him. “Last time I checked, you were a guitar player.”

“Don’t worry about it; I’ll show you when you get here.”9

(BACK TO THE BOOK…)

He says,

“The cats love to play, but they only sing a little bit, and there’s not a whole lotta writin’ goin’ on. So, he says, ‘come and sing, and write, and round it all up and send it in some sorta direction.”

Gregg called the above “the finest compliment I ever had.”

“Which is, I do hope, what I did. I tried, anyway.”

This isn’t even up for debate in 2024, much less 1975 when Gregg gave the quote.

His arrival in Jacksonville glued Duane’s project together, solidifying a lineup that forever transformed southern music.

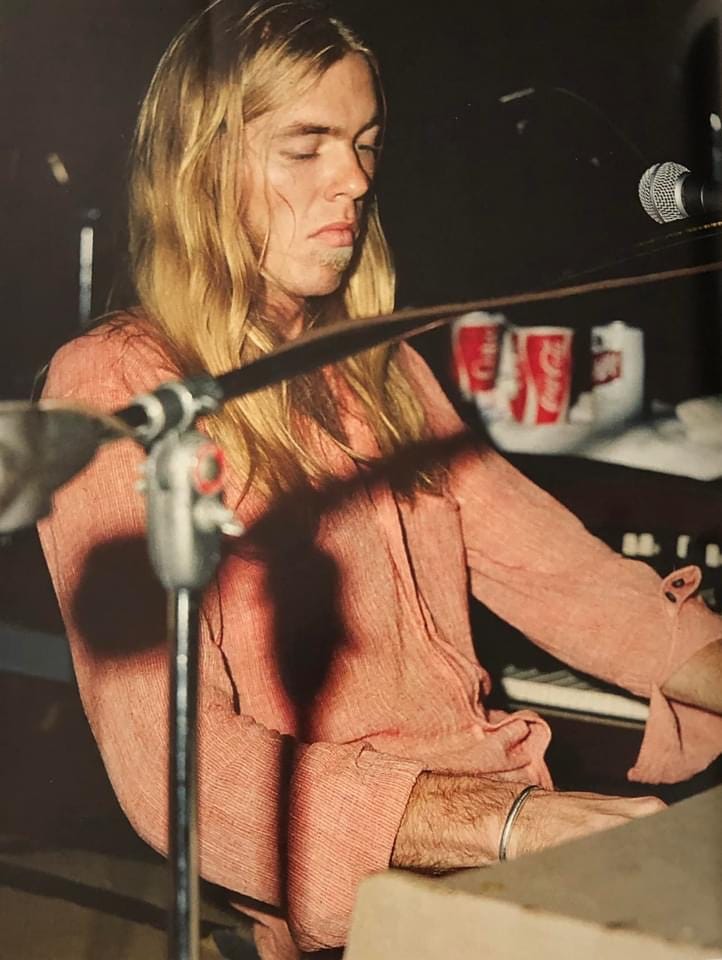

“He says, ‘The only stipulation is, you gonna have to play organ.’ And I’d been playing guitar for 14 years. I’d sat behind a Hammond B-3 maybe three times in my life; an organ player I was not.

But he says, ‘If you come back here, we’ll even arrange to buy you an organ.’

That’s all it took. I said, ‘Doctor, an organ player you want, an organ player you got.”

I’ll pick up the story from another source.

“I had never sat behind one of them but one time. And that one time I sat behind it I wrote ‘A Cross To Bear’ and ‘Dreams.’ All I ever wanted was a Hammond B-3. So, I had to do it, you know.”

It worked out well, dontcha think?

Here’s how Derek Trucks put it. “The rhythm section in the Allman Brothers was always this propulsive, mysterious thing that was part of the magic, but the sound of Gregg’s B-3 was a huge element to that. The intro to ‘Dreams,’ that stuff gives you the chills before anything else shows up—before the lyrics and the Duane solo, when it’s just the drums and the sound of Gregg’s B-3. That’s what probably drew me in without even knowing it. It’s sneaky good.”

And ponder a second the melancholy of “Dreams” and “Cross to Bear”

The two songs Gregg wrote on the B-3, the only songs he brought to Jacksonville that band adopted.

Both songs carry despair and a world-weariness that belied his youth (he’d just turned 21). Each was a mainstay of the Allman Brothers’ repertoire. When Duane called him from Florida, Gregg was at the point of suicide.

“My songs are wide-awake dreams and wide-awake nightmares.” Gregg once said.

Indeed.10

“The day I got to Jacksonville they were set up at Butch Trucks’ house.11 I was scared to death. It was hot as hell outside. The people in the band didn’t know me. I felt they were acting strange; I thought, well, damn, they’re just being nice to me ‘cause I’m Duane’s brother.”

Said Gregg, “Of course, when you walk into a room and everybody knows everybody else except you, it’s tough, especially when you’re as shy as I am. It was real tense in that room. You could have cut it with a knife.”

“Duane says, well, we’ve learned two songs. Of course nobody sings ‘em yet. Well, Oakley here, he sings ‘Hoochy Coochie Man.’12 And they played it, and man, did he ever sing it. Then they played ‘Trouble No More.’ And when they were through, I was ready to get back on the plane.

I told Duane, ‘Man, that’s the finest singing I have ever heard, and what I am doing here I do not know. There’s nothing I could do to possibly make that any better, and I just cannot cut the gig.’

Duane went right at his brother’s heart.

“He said, ‘Well, you little weakling, you can snivel on out of here; but I know you can cut it, and you know you can cut it, and all it takes is a little trying!’

He says, ‘If you don’t try, don’t call yourself my brother, because l’ve bragged to these people, and I’ve bragged to ‘em about you.

“Later, I found out, he’d told them, ‘You think we got a band now, wait ‘til my little brother gets here.’ So what it was, instead of ignoring me that day, they were waiting for something really incredible to happen.”

“And it really really hacked me off when he crawled on me like that. So I went in the back room and wrote down the words of ‘Trouble No More,’13 and I came back and sang ‘em, just as hard and gutsy as I could. And they were thrilled. And I did cut it.”

“It was such a pleasure playing and singing with them. They had never heard any vocal over their music, in the three months they’d been together.

Duane had planned it that way; he was getting the whole band so it would be already a little rehearsed by the time he called me.

I felt so good about everything, in the next week or so I wrote ‘Whipping Post,’ ‘Blackhearted Woman,’ and ‘Every Hungry Woman” and I wrote on the average a couple songs a week, from then on.

It wasn’t three months, probably wasn’t even 3 weeks total. But yeah, they’d never heard vocals like Gregg’s before. He was just what the band needed.

Don’t miss Gregg’s observation that that’s exactly how Duane planned it. He pulled the band together, worked it out a bit, and called Gregg to “round it up and send it somewhere.” The band lived on for 45 years.

Up next in this series…

The Allman Brothers Band moves to Macon, meets Mama Louise Hudson at the H&H Restaurant, and records their debut album.

Call 988 if you’re struggling with mental health. You matter, remember that always.

Ya tu sabes.

Link in case you missed it above here it is again. “Call Gregg, we need a singer.”

No shit.

This is from Galadrielle’s wonderful book Please Be with Me, that every Long Live the ABB reader simply must own.

Gregg’s memoir My Cross to Bear, p145.

Not Butch’s, it was Berry and Dickey’s house.

“Hoochie Coochie Man,” with Oakley on vocals appeared on Idlewild South in 1970.

For an idea of what “Trouble No More” sounded like, check the demo recorded in April 1969 in Macon, which I wrote about here.