The Sky is Crying

When it comes to death and grieving, I’ve learned a lot from the Allman Brothers Band.

I’ve written about it here at the Crossroads…

And, of course, in Play All Night!

The band’s reaction to Duane’s death reflected a fierce determination to carry on his music in the face of tremendous grief.

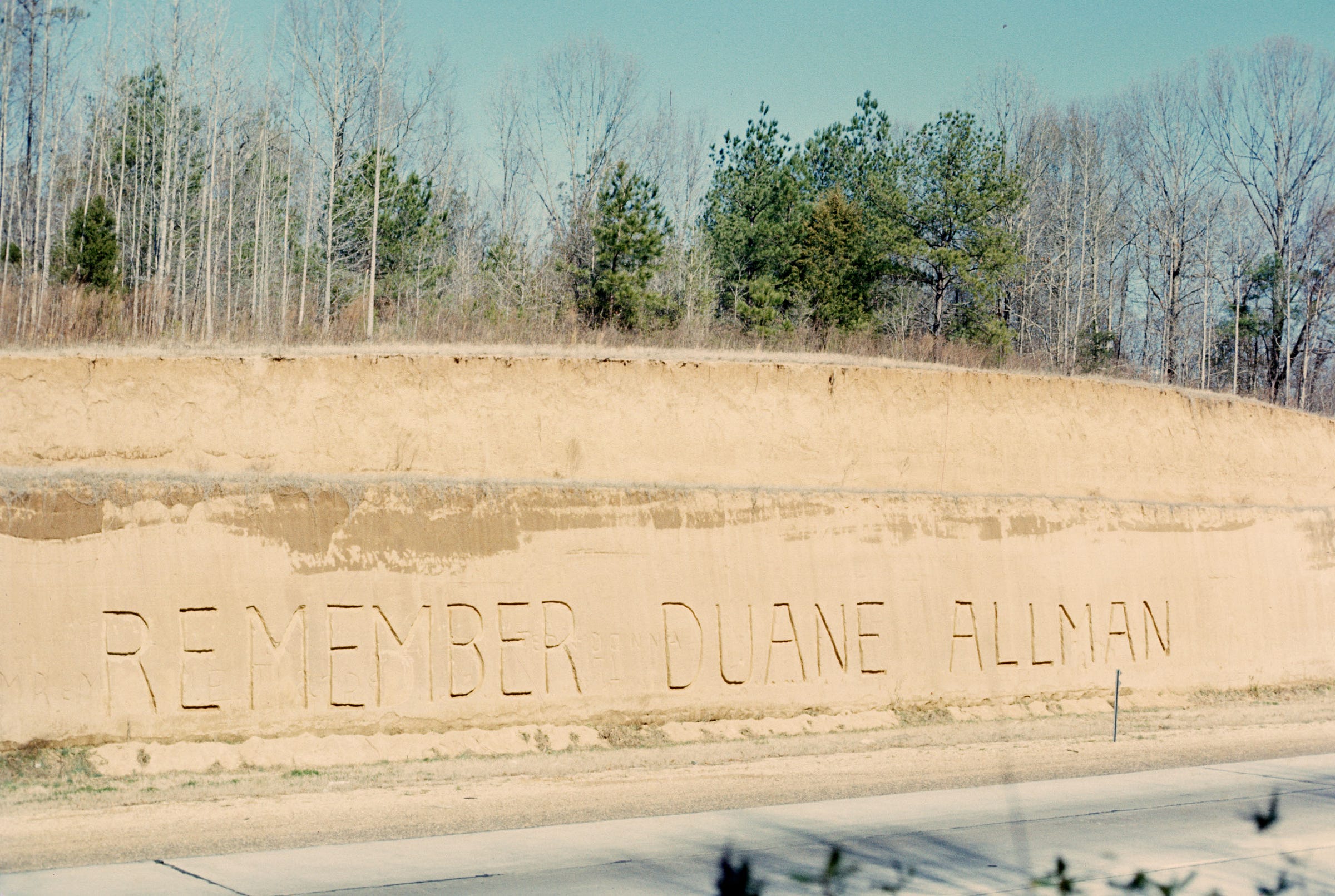

Duane Allman 11/20/46-10/29/71

Excerpt from Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East.1

Spirits were high in Macon in fall 1971.

As At Fillmore East stormed the charts, the group had begun to lay down tracks for its next album. Duane’s accident on October 29 happened just after his return from a rehab stint for heroin.

The band’s fourth album, Eat a Peach, is epilogue to Duane Allman’s remarkable career and the final chapter of the original era of the Allman Brothers Band.

Duane’s devastated bandmates honored him with an enduring commitment to his vision. They channeled their grief the only way they knew how: through music.

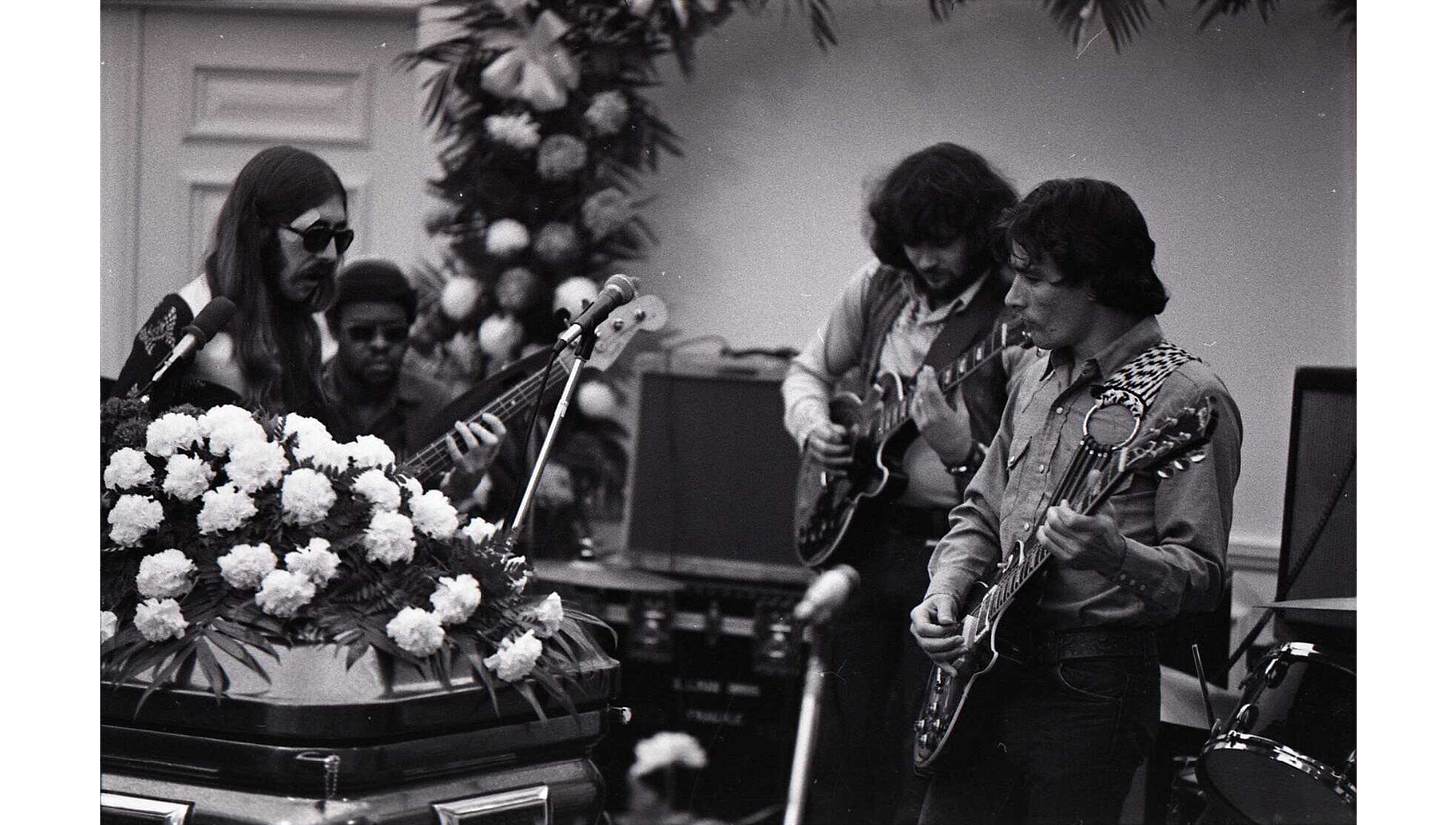

On November 1, they played at Duane’s memorial service. Three weeks later, they embarked on a nationwide tour as a quintet.

Immediately following the memorial service, Gregg, Dickey, Berry, Jaimoe, and Butch returned to Criteria Studios in Miami to complete Eat a Peach. Released February 12, 1972, it was the ABB’s second consecutive double album.

Though the band was in transition, Eat a Peach is a fluid, cohesive musical statement.

A mixture of live and six studio tracks, the record presents three separate sides of the ABB: the original band live and in the studio and the five-man band in the studio. The album demonstrates maturity and creativity. Tracks reflect influences of western swing and country (“Blue Sky”), folk (“Melissa” and “Little Martha”), electric blues (“Stand Back”), jazz-rock (“Les Brers in A Minor”), and psychedelia (“Mountain Jam”).

Duane appears on sides 2, 3, and 4, two of which feature the thirty-minute-plus “Mountain Jam” that faded out at the end of “Whipping Post” on Fillmore East. Side 3 has two live tracks, “Trouble No More” from the Fillmore sessions and Sonny Boy Williamson’s “One Way Out,” recorded at a later Fillmore date, and three studio originals, “Stand Back,” “Blue Sky,” and “Little Martha.”

Eat a Peach delivered two important messages.

First, they missed their leader, they would carry on without Duane. Gregg sang in the album’s opener, “I still have two strong legs, and even wings to fly.”

Second, they would never forget Duane. Dedicated to a Brother, Duane Allman, read the gatefold.

Long may they boogie

Eat a Peach spent forty-eight weeks on the charts, reaching number 4, nine spots higher than At Fillmore East.

“Duane is gone—but the Allman Brothers Band are still cooking,” wrote Tony Glover. “Long may they boogie.”

“Side One, sans Duane,” noted Hal Pratt, “exhibits evidence of the band’s immortality and ability to continue in its unique musical tradition.”

“The Allman Brothers Band has emerged unscathed and unchanged in their talent for originality,” said Dave Stitz.

“The group is not the same without Duane,” Glover wrote, “but it’s still the Allman Brothers. It’s not a question of being ‘as good’ or ‘not as good’—rather it’s just a difference.”

“There is no overt reckoning with Duane’s absence,” said Steven Lasko. “There couldn’t be a finer tribute either.”

“So soon the five-man Allman Brothers began to play again—what else could they do?”

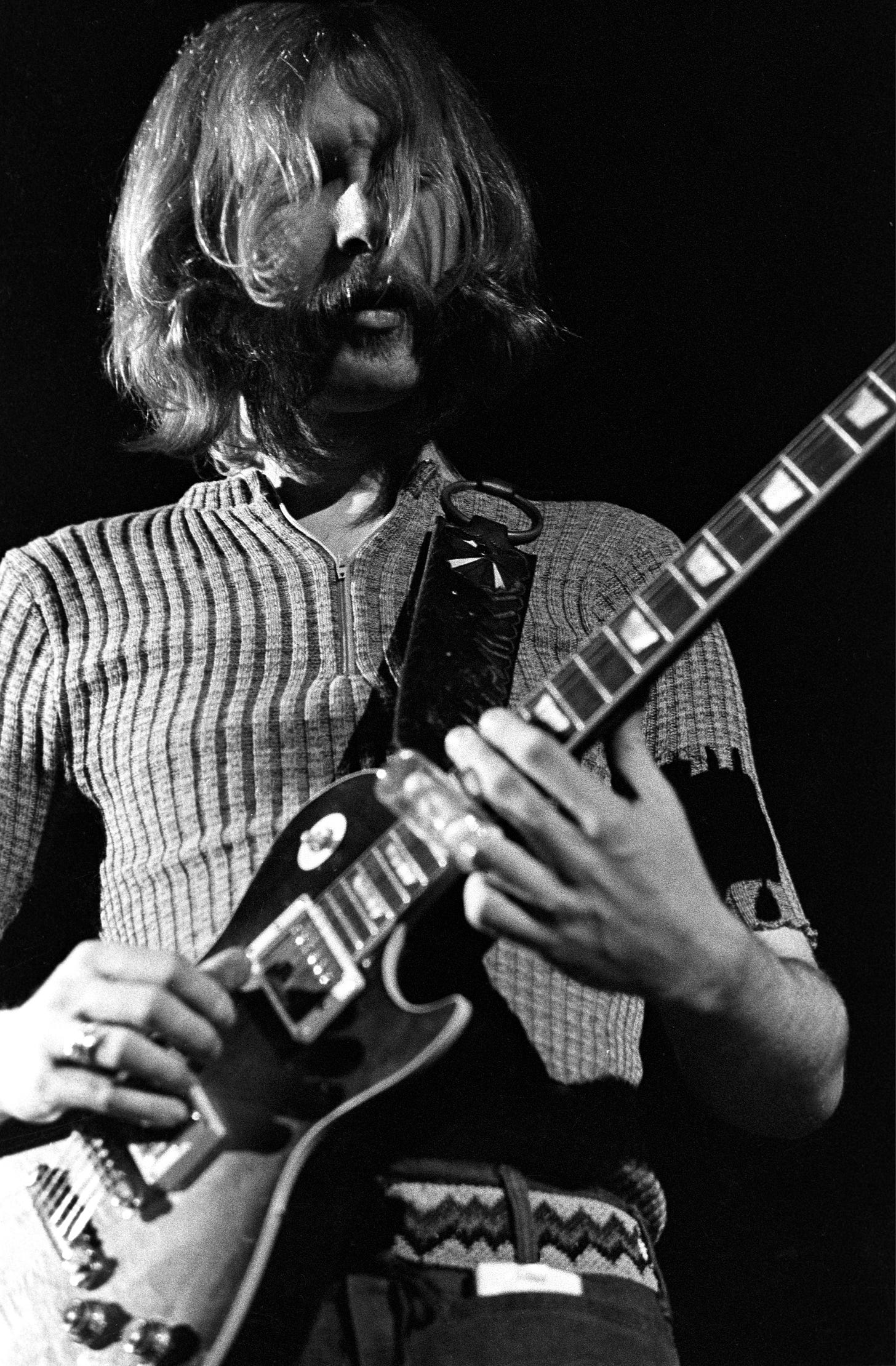

Though Duane’s death ended their musical collaboration, his bandmates carried his spirit with them musically.

It was the way he’d best appreciate.

“Most voids ache to be filled, and music can fill many because it can contain so much; sorrow, celebration, anger, love—and always the joy of just plain getting it on,” said Glover.

“So soon the five-man Allman Brothers began to play again—what else could they do?”

Gregg Allman

“Look boys, if you were thinking about stopping, don’t. We need to get back to Miami, because we’ve got some unfinished business down there. If we don’t keep playing, like my brother would’ve wanted us to, we’re all going to become dope dealers and just fall by the wayside. I think this is our only option.”

Butch Trucks

“There was never any thought of not continuing, because Duane had given us the religion, and we were going to keep playing it. We knew that this was the last music Duane recorded2, and we knew that we had to finish it up so that we could get it out to the people.”

Gregg

“Losing Duane really slammed Dickey too, but he didn’t show it. We didn’t see too much of Dickey after my brother died…. He come back in for dinner, and he’d be OK… I think he really cared about my brother.

Dickey Betts

“It took me a long time to really accept it. Your mind kinda protects you in that way.... I would have dreams that we were touring and we’d run into Bonnie & Delaney and Duane was playing in their band.... It was a devastating event for all of us and it’s a wonder that we kept the band together and continued on, but we did.

The first feeling that all of us had, “It’s over”—as far as this music is concerned. We were trying to console each other in the days preceding the services and the best way we could do it was to play music. One thing led to another and we slowly realized that the best thing we could do was stay together... There was so much creative power in that group that that’s the only way we were able to continue on without Duane.”

November 1972

Jerry Wexler gave the eulogy at Duane’s funeral service in Macon November 1, 1971.

The band performed as well. In a fitting tribute, they played Elmore James’s “The Sky is Crying.”3 Gregg performed a solo version of “Melissa,” Duane’s favorite. Thom Doucette, Dr. John, and Duane’s good friend Delaney Bramlett (between Dickey and Jaimoe) all sat in.

When the music ended, Dickey took off Duane’s Les Paul, placed it in its case, and leaned it beside the casket.

On November 22, they played an emotional first gig as a quintet, at C.W. Post College4 in Greenvale, NY. November 25, the Allman Brothers Band headlined Carnegie Hall, a gig Duane had been greatly anticipating.5

After the first show, Nick Chernock wrote:

“‘Statesboro Blues’ ignited the place as the song always does, and they followed it with ‘Done Somebody Wrong.’ It was then that Duane’s absence really became apparent. The two guitars playing off each other in spiraling bursts were no longer there.

Dickey Betts, alone now, played as if the pressure was easing with each note. For a moment, I thought he was moving his head from side to side as Duane did when he used to mouth the notes, which was a very strange sensation. The music flew by—“Stormy Monday,” with Gregg playing as I’ve never heard him, “Whippin’ Post,” “Hot ‘Lanta,” and on through two encores.

Just before the last encore, Gregg thanked the enthusiastic audience for helping them back. ‘Skydog’ Allman was dead, but the Allmans played on.

The best band in the land.”

Despite their pain, Duane’s devastated bandmates played brilliantly.

In honor of Duane and the band’s commitment to carry on in his absence, Gregg changed the last line of “Whipping Post” from “I feel like I’m dying!” to “There’s no such thing as dying!”

Butch said, “We played some blues, let me tell you. We still do. There’s one place in our set and it’s for Duane. I’m not going to tell you exactly what or where it is, but it’s always there. I feel it every night we play. We all do.”6

Jaimoe

“I really can’t remember anything about any of those shows. We just had to play and everyone played and you really didn’t know what you missed more about Duane—being on stage with him or just life in general.”7

Audiences loved the 5-man band. “Sometime after three the band launched into the obligatory finale ‘Whipping Post,’” Bill Brina wrote. “And then you knew why they’re staying on tour. The music goes on.”

Said Glover, “They can still cook and burn with all the flat out soul that they’ve become known for. The band is tight, together, and full—and though it’s sad not to hear the dialogue between Duane and Dickey’s guitars, you soon realize that a whole new conversation is going on between Dickey and Berry.”

Oakley took Duane’s death the hardest. Playing was his only relief and his bass took on a renewed force in Duane’s absence.

Berry blunted his pain in a haze of drugs and alcohol and died in a motorcycle accident November 11, 1972.

The accident killed Oakley, but Berry really died of a broken heart. Duane’s death mortally wounded his spirit, and Oakley died before he recovered from the loss. He and Duane were brothers, musical soulmates. “He could not abide a world without Duane Allman,” said Butch.

Duane and Berry were buried beside each other in Macon’s Rose Hill Cemetery. The plot has grown to include Gregg Allman and Butch Trucks.

Lagniappes

Dickey Betts & Butch Trucks 1984 interview. I’ve got this queued up to the 10-minute mark, where Butch and Dickey discuss Duane’s death and its impact.8

5-man band playlist. This is “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” from the Mar y Sol Festival (Dreams box set) and two shows: 2/12/72 Macon and 4/7/72 Syracuse9

Until next time…

Get yers and support an independent bookstore: playallnight.longlivetheabb.com.

“Stand Back” “Blue Sky” and “Little Martha” from Eat a Peach.

One of the very few times the group played it. It appeared 53 times between 2001-2014.

Now Long Island University Post.

A secret Butch took to his grave, as far as I know but if you wanna hear some deep blues, check out “You Don’t Love Me” and “Stormy Monday” from the 5-man band.

Dickey Betts & Butch Trucks 1984 interview

As long as his music and spirit continue to live on.....

Thank you for the medicine, good Doctor. It helps..