Southern Gothic meets the Southern counterculture—the Allman Brothers Band

I call this newsletter Conversation from the Crossroads. Crossroads is intentional, a nod to Robert Johnson’s “Cross Road Blues.”1 Using the “Crossroads of Southern music, history, and culture” motif, gives me a lot of room to interpret the band’s influence and impact.

This is my take on one particular crossroads: the Southern counterculture and the Southern Gothic tradition. I explored this concept for a presentation and adapted it for print here.

Here is video of the session (warts and all) for those who prefer that medium:

Let’s start at the crossroads

The crossroads carries a tremendous amount of symbolism in the American South. Its origins trace to the tales of enslaved Africans.

The crossroads was a sacred space where West Africans journeyed to invoke gods. In America, as these African traditions merged with Christianity, the god of the crossroads became the ultimate trickster: Scratch, Legba, Satan.

It’s at the crossroads Robert Johnson allegedly sold his soul to the devil, a legend that reverberates in popular imagination today, well beyond blues and roots music.

Salvation in music

The Allman Brothers Band found salvation in music and in the Southern counterculture. Their story is one of resilience: cultural, economic, emotional, spiritual, and existential. The band was a microcosm of the South, its contradictions, its struggles, and its beauty.

Emerging from Macon, Georgia, in 1969 and the years immediately following the 1964 Civil Rights and the 1965 Voting Rights Acts, the Allman Brothers Band were an integrated band that clashed with the expectations of southern society.

They spoke of music in spiritual terms and pursued music with religious fervor. Songs like Gregg Allman’s “It’s Not My Cross to Bear” addressed religious themes.

Their repertoire included “Stormy Monday” (made most famous by Bobby Blue Bland):

“Sunday I go to church, I kneel down to pray.

And this is what I say.

‘Lord have mercy! Lord have mercy on me.’”

At the crossroads, Robert Johnson called out to God:

“I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees

Asked the Lord above, ‘Have mercy, now, save poor Bob if you please.’"

Gregg found the crossroads haunted in “Melissa”…

“Crossroads, will you ever let him go?

Will you hide the dead man’s ghost?”

…existential crisis in “Dreams”…

“Went up on the hilltop, to see what I could see.

The whole world was falling, right down in front of me.

I’m hung up on dreams I’ll never see.”

…and torture in “Whipping Post”2

“Sometimes I feel…like I’ve been tied to the whipping post!

Good Lord, I feel like I’m dying!”

A Southern Gothic primer

Rooted in the humid, Spanish moss-draped landscapes of the American South, Southern Gothic literature emerged from the 18th and 19th century (European) Gothic tradition. Instead of castles, the setting is the American South’s crumbling plantations—a Southern society grappling with the specters of slavery, the Civil War, and the Lost Cause.

Southern Gothic confronts the South’s romanticized past with the realities of these unresolved conflicts. It balances darkness with redemption, embracing the complexities of human experience in stories that critique and celebrate southern identity.

To the Allman Brothers Band, these are not abstract ideas; their Southernness is essential. They embody the region’s contradictions—Patterson Hood’s “duality of the southern thing”— and offer a vision of hope and unity.3

Themes of a haunted past, loss, decay, moral ambiguity, cultural tension, alienation, redemption, and resilience resonate throughout their story.

Death hovers like a cloud.

Three of the six members grew up fatherless. As toddlers, Duane and Gregg lost their father, a D-day veteran who was killed in a robbery attempt. Drummer Jaimoe also lost his father as a youth.

Twin tragedies further mark the story: the deaths of Duane Allman and Berry Oakley in consecutive years: 1971 and 1972.

Redemption: Hittin’ the Note

Hittin’ the note was the band’s mission.

They sought spiritual transcendence through music.

For the Allman Brothers Band, music was an outlet for self-expression. The band challenged norms with an interracial lineup in a South still struggling to fully integrate.

Their music fused rock with blues, jazz, country & western, string music, folk, even classical. The Allman Brothers played contemporary American music built on Southern musical traditions, a jazz-inspired, improvisation-heavy attack.

As Duane said,

“These six guys have always worked for one sound, one direction, but everyone plays like he wants to play. He just keeps that goal in mind. If you know what you do and you’re satisfied in your heart that you’re doing it, you ain’t gonna have no problems.”

They sought deeper connection with each other and with audiences.

Remarked Butch,

“We’re up there playing for ourselves first and foremost. I’m not getting myself off. How can I expect anyone else to get off on it? I start with myself, then move to the guys in the band and then we start communicating. We kick it in overdrive and go into places we can’t go by ourselves.”

“Hittin’ the Note” was Berry Oakley’s phrase

What Dickey Betts called “getting down past all the bullshit, all the put-on, all the acting that goes along with just being human. Getting right down to the roots, the source, the truth of the music. Letting it happen, letting that feeling come out.”

Said Oakley:

“Hittin’ the note is hitting your peak. . . the place where we all like to be at, you know? When you’re really feeling at your best, that’s what you describe as your note. When you’re really able to put all of you into it and get that much out of it.

There’s some special places we play and every time we go back, the vibes are there and it ends up happening again. We’ll end up playing three or four hours, and when we finish, I’ll be so high I can hardly talk. When you start hitting like that, the communication between the members of the band gets wide open. Stuff just starts coming out everywhere.”

As Jaimoe described it, “Times when I was so at peace with what I was playing, that my spirit left my body right on stage.”

Audiences heard it too. The Allman Brothers are “a physical and spiritual experience. Six guys playing as a giant organism,” wrote Philip Lane.

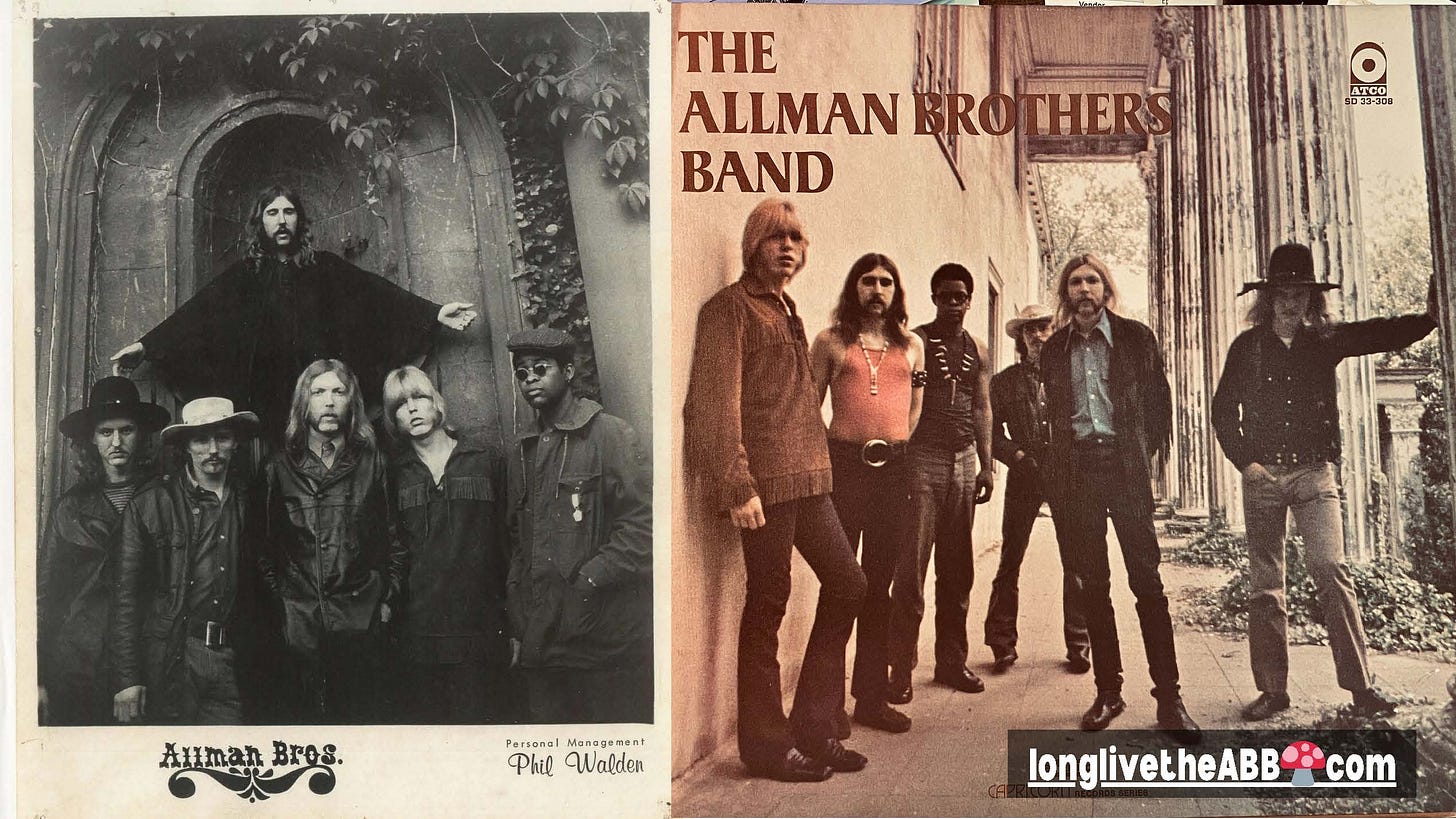

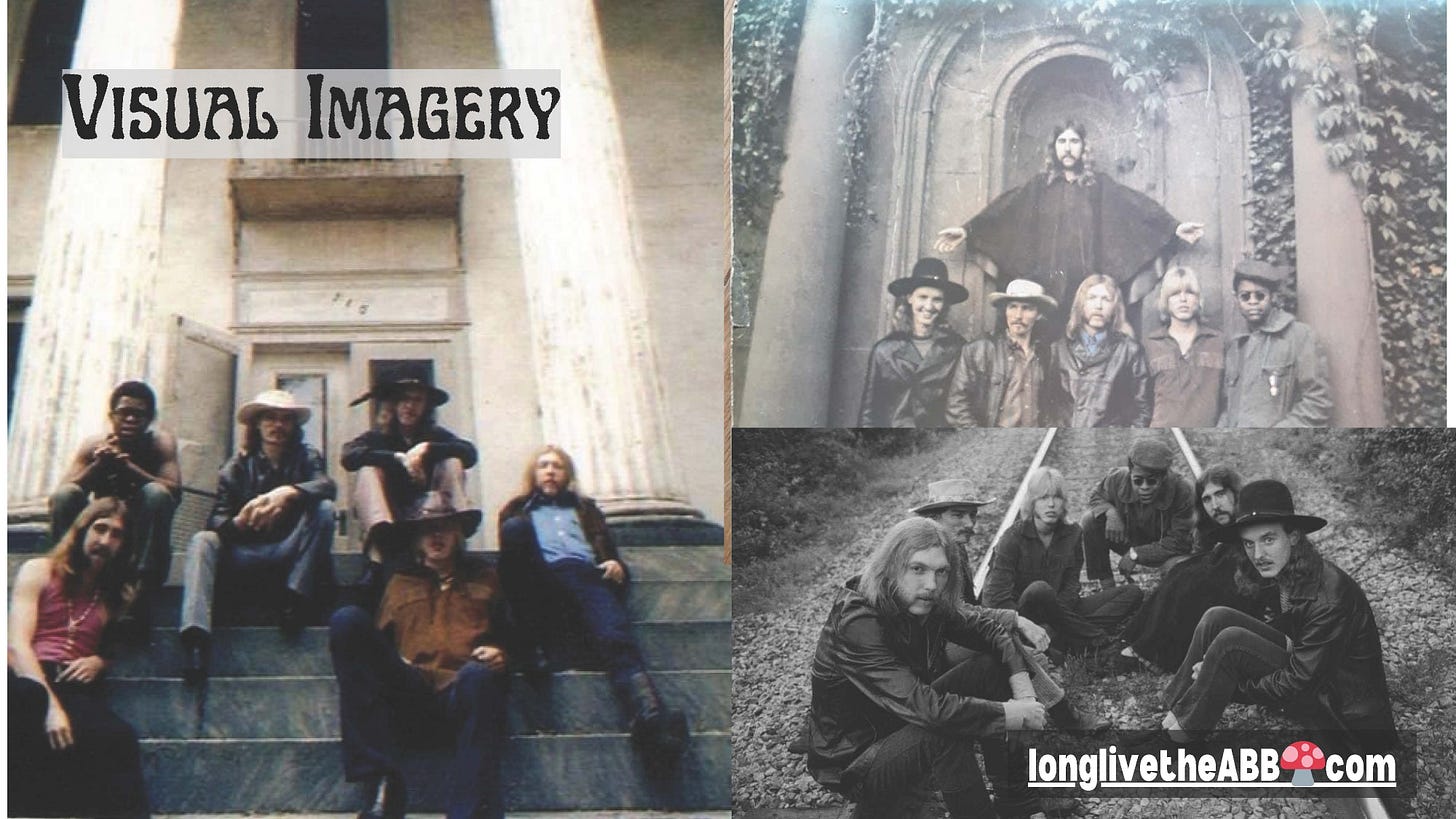

The band exemplified Southern Gothic themes in its visual imagery

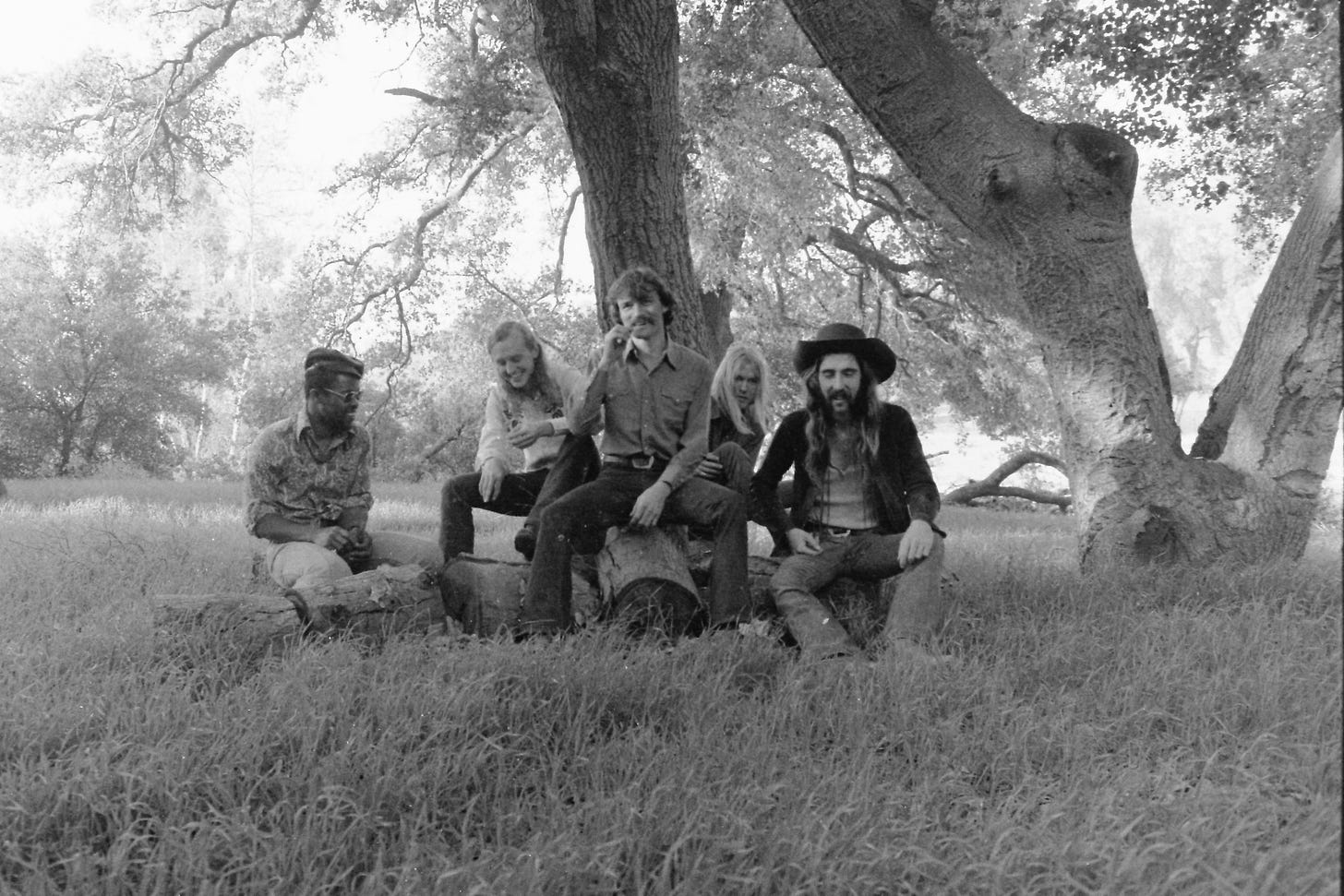

The photo on the left is the same site as the band’s first album cover.

This is actually the 1855 home of a prominent cotton plantation owner. (It was in a state of disrepair in 1969 when they took the photographs.)

The image in upper right here is the back cover of the first album, and that’s from Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon.

Berry Oakley is standing in an alcove of a mausoleum for Joseph Bond, who at one point was one of the largest slaveholders in the United States. The photo on the railroad tracks is just past the Bond tomb.

The photos were taken in summer 1969 as the band was preparing its first album.

They look like outlaws from a different time, a band of warriors ready to take on the world, which was true.

The Allman Brothers Band was on what became two-plus years of relentless touring, spending more than 300 days a year on the road in 1970 alone.

Success came in 1971

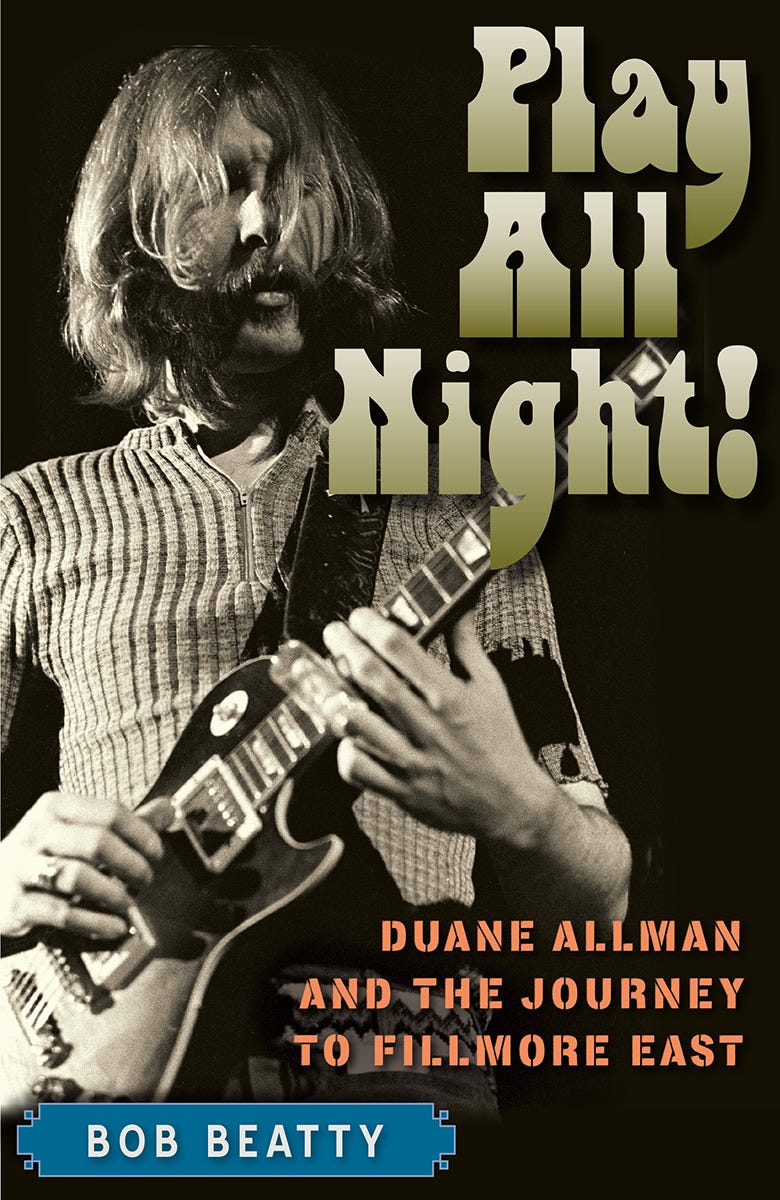

In March, they recorded their masterpiece At Fillmore East in New York City. Released July 6, the album hit gold by October 25.

It was a remarkable achievement for a band that had barely sold 150,000 units in their first two records.

Duane’s death

On October 29, just days after receiving the news that the record was a breakthrough smash hit, their leader Duane Allman was dead in a motorcycle crash.

He was three weeks shy of his 25th birthday.

Duane’s devastated bandmates honored him with an enduring commitment to his vision. The band channeled their grief in the music.

On November 1, they played his memorial service.

Then they embarked on a nationwide tour as a quintet.

As Butch Trucks said, “We were playing for our lives trying to make sense of it all.”

Said Dickey:

“The whole thing was uncomfortable at first. You know, you’re up there and you’re not really happy about the situation to start with, but yet, you can’t go up there all bummed out, either. It was a thin line to walk, and it was something that had to be done with reverence.

At the same time, playing music felt good after going through Duane’s death. It felt good to get back out and play, because that’s what we do, you know? There had been some talk about not playing as a group anymore—we had some talks about that.

Everybody in the group had mixed emotions about it, about everything—we were confused. It was decided that if we could do it honorably, and if we could sound good enough, it wouldn’t be detrimental to the band’s reputation or Duane’s legacy. As it turned out, we played really well.”

The band found healing in music, but three hours onstage only provided temporary relief. Duane’s death had a profound effect on everyone. Berry Oakley was most distraught. “Duane’s death destroyed him,” said Gregg. “Berry Oakley’s life ended with my brother’s life. Never have I seen a man collapse like that.”

Oakley blunted his pain in a haze of drug and alcohol and died in a motorcycle crash a stone’s throw from where Duane died a year earlier: November 11, 1972.

Since 1972, Duane Allman and Berry Oakley have been buried beside each other in Rose Hill Cemetery. The plot has grown to include four of the six original members: Duane, Berry, Gregg, and Butch Trucks.

Rose Hill

Rose Hill Cemetery, with its terraced tombstones and moss-covered trees, grounds the Allman Brothers Band’s story in Southern Gothic themes of decay, memory, and beauty.

Established in 1840 along the Ocmulgee River, the cemetery is famous for its classical revival garden layout. But its beauty belies its past. The 50-acre site is the final resting place for generations of slave-holding Maconites and their descendants, including 10 acres set aside for enslaved people.

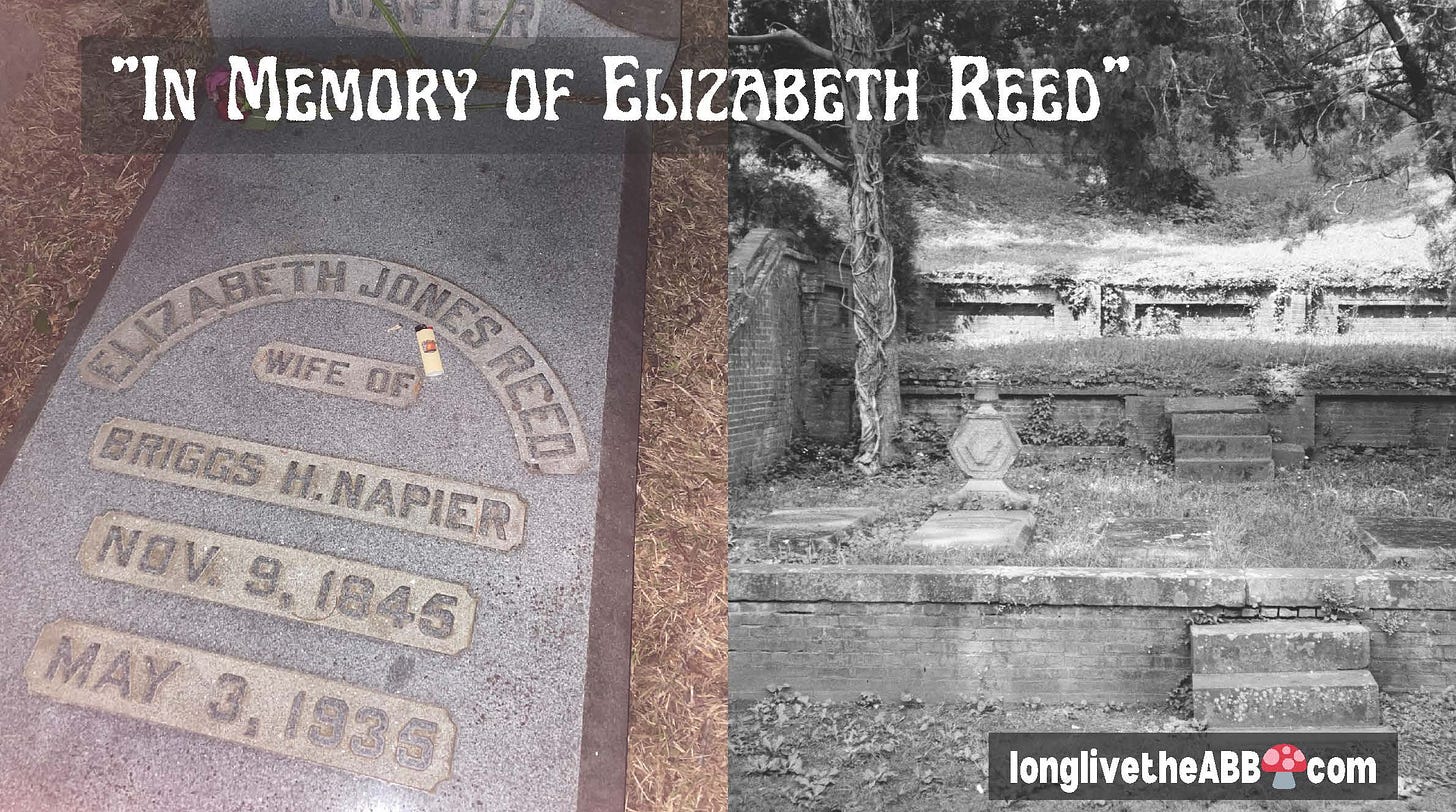

Rose Hill was a favorite hangout for the band in their early days, a place where they roamed, reflected, and found inspiration. Most notable is Dickey Betts’s instrumental “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.” Betts named the song for Elizabeth Jones Reed Napier, the wife of a Confederate officer. Her tomb was Dickey’s rendezvous spot with Boz Skaggs’s wife Carmella, a torrid affair that inspired the song’s haunting minor key melody.

“In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” is an indelible part of Allman Brothers Band mythology, a link to the beauty, tragedy, complexity of Southern history and the transcendent power of their music.4

And then there’s this striking coincidence connecting past to present.

Elizabeth Reed died in 1935, just steps from 2321 Vineville Avenue: the Big House, which served as the Allman Brothers Band’s communal home from 1970-73. (It is now an Allman Brothers Band museum.)

The Napier family had tremendous wealth. The Big House sits on land that originally belonged to Reed’s husband’s grandfather. Her father-in-law was infamous as the largest individual investor to the Confederate cause in 1861.

These intersections of genteel Southern society and a rebel band of rock & rollers define the Allman Brothers Band story.

The struggle helped shape the modern South.

Touring in the South

As an interracial band, the Allman Brothers directly challenged the white supremacist norms of Southern society. Their integrated lineup playing Black-influenced music was a bold statement of inclusion and creativity rather than division.

In an era fraught with danger for long hairs, the group made its name on the road. And touring for the Southern counterculture was an intense experience.

As Bruce Hampton said, “It was life or death. You’d stop at a gas station and you’d wonder if you were going to die. That’s no joke. If you had long hair, you were a target.”

Traveling with a Black drummer brought additional issues in a region gradually adjusting to desegregation.

And though Jaimoe has never spoken of the indignities he experienced, his bandmates have. “We were always a little on guard for someone to mess with him,” roadie Red Dog said. “We got messed with a lot.” Said Betts, “I was horrified at that kind of thing.”

Their support of Jaimoe is significant.

Gregg described “perennial redneck questions: ‘Who them hippie boys and who’s the n——r in the band?’ We dealt with that second question quite a bit. Keep in mind, this was the 1960s, we were in the deep South, so having a black guy in the group came up a lot. But Jaimoe was one of us and we weren’t going to change that for nobody.”

Further, with the psychedelic mushroom as their logo, the Allman Brothers Band distanced themselves even more from polite Southern society, aligning themselves with the Southern counterculture.

Redemption in Performance

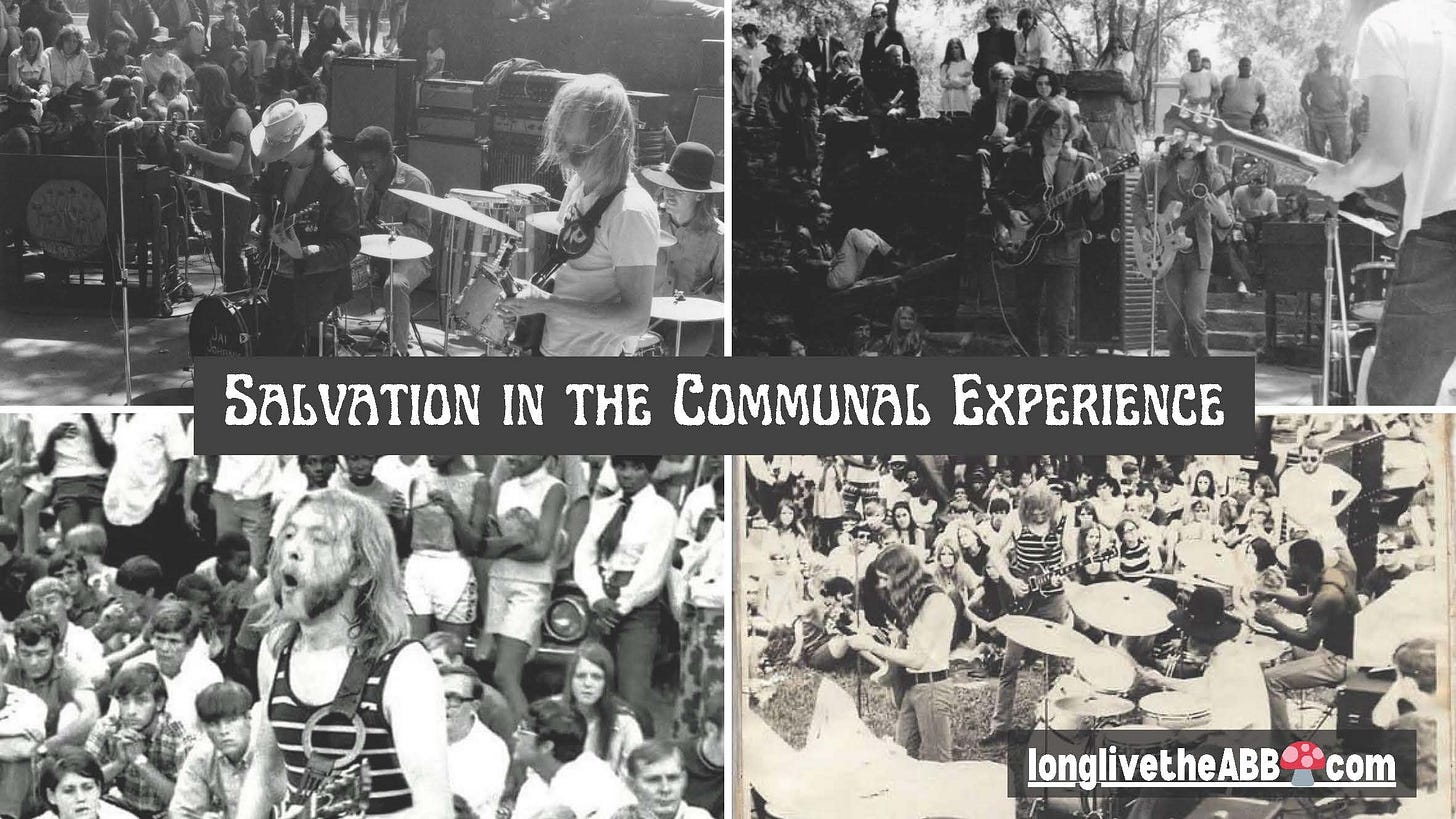

I picked these photos (all from 1969) to show the importance of the communal ritual of live music from the earliest days of the Allman Brothers Band.

An Allman Brothers concert was more than entertainment. It was a ritualistic performance, a spiritual revival. Wrote Miller Francis Jr. “You don’t listen to the Allman Brothers. You feel it. Hear it. Move with it. Absorb it.”

Improvisation made the performance once-in-a-lifetime. Far from passively listening, the audience were active participants.

As Dickey said,

“We were just trying to make the audience be consumed by what we’re doing and if we can make that magical kind of music happen. They don’t know what’s happening exactly. They know that we’re really focused on what we’re doing, and it sounds good and the energy is good. What they will do is forget about this and forget about that and have fun. Just simply have fun for two or three hours.”

The live experience was proof of a foundational concept: music as a communal experience with and for the audience.

It was a formula the band followed for 43 years without their founder, Duane Allman, and 42 years after the death of Berry Oakley.

Crossroads, will you ever let him go?

In the final verse of “Melissa,” Gregg is at the mercy of the same haunted crossroads where West Africans sought gods and where Robert Johnson sold his soul.

The Allman Brothers Band stands at a different intersection their musical take on the South’s own crossroads of beauty and decay and struggle and salvation.

Lagniappe

Youtube Playlist

Here’s all the cuts referenced in this post: Playlist: Southern Gothic Counterculture.

It includes an acoustic “Melissa” from the 90s and “Liz Reed” from 9/19/71 SUNY Stony Brook.

Thanks for being a paid subscriber to Long Live the ABB.

This post was originally reserved for paid subscribers of Long Live the ABB.

I’m probably not the only one who first heard Cream’s version.

A reminder of this wonderful “Whipping Post” video, this is the cleanest footage I’ve ever seen:

From “The Southern Thing,” on Drive-By Truckers’ Southern Rock Opera (2001).

Here’s a longtime favorite “Liz Reed,” 9/19/71 SUNY: Stony Brook

I think this band and this music just had to happen...from all of the influences that you mention Bob, this was a stew that was looking for the right 6 master chefs to get together in the kitchen and start cooking together. The "right" players found each other and created magic together. Macon became the perfect home base for them as the horror of slavery and then the fight for freedom from it was such a powerful influence in all of the African American music that was created and evolved there over the years. I can't imagine the arc of American music without the Allman Bros. Band.

They were in Jacksonville in 1969 not Macon….