A Berry Oakley Thunderfest

The Allman Brothers Band at Manley Fieldhouse 4/7/72

Welcome to Long Live the ABB: Conversation from the Crossroads of Southern music, history, and culture.

Today’s post (an edit of one originally behind the paywall) is a deep dive on the Allman Brothers Band’s archival release Manley Fieldhouse, Syracuse University April 7, 1972. Queue it up here and read along.

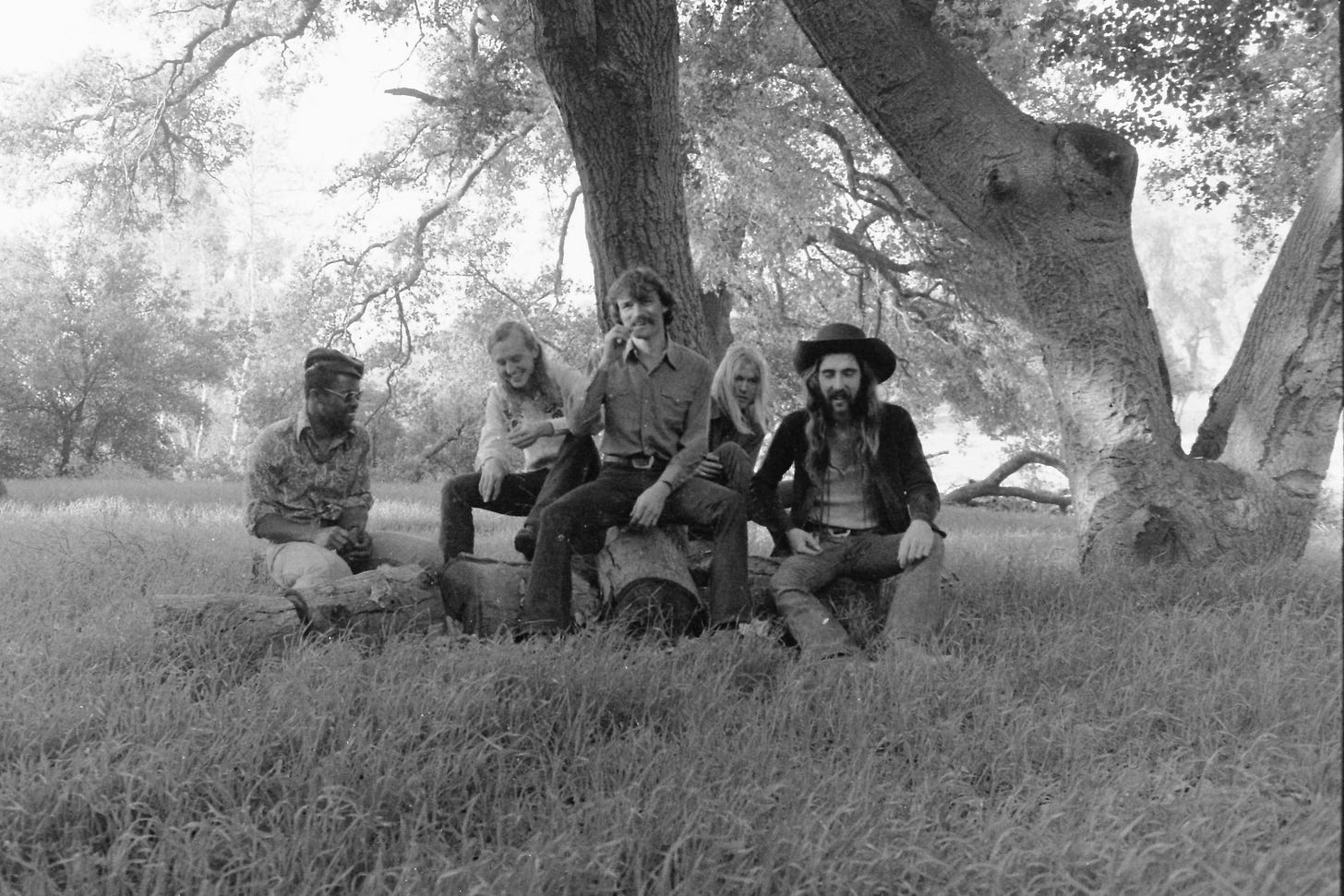

The 5-man band

In the wake of Duane’s death, his surviving bandmates finished Eat a Peach and embarked on a massive tour as a quintet. This era of the Allman Brothers Band has always fascinated and inspired me.

I’ve have thought/written about the era a lot. Other than Play All Night, here’s 2:

And if you don’t want to read it, here’s me riffing on video about Eat a Peach and a longer-form video essay on the album1

I’m astounded every time I think about it. How can anyone in so much pain get up and perform at any level, much less a HIGH level (more on that in a bit).

It’s taken me some time to digest my thoughts on the release. It’s been awhile since I’ve given this show a deep dive. Listening gave me a renewed respect for this lineup.

What it says to me, what it’s always said to me, is how much music meant to them. They poured out their grief through playing. Honoring Duane’s memory as best they knew how, as he would have wished.

Literally.

Here’s Butch

When Duane came back from King Curtis's funeral, he was thinking a lot about death and he said many times, “If anything ever happens to me, you guys better keep it going. Put me in a pine box, throw me in the river, and jam for two or three days.”2

On just about any level you can think of, it was devastating. What kept us going was the bond that forms when you have to deal with that kind of grief. Also, we did it for his sake as much as ours. We had just gone too far, and hit so many new plateaus in what we were doing, to simply quit.

There wasn't any other way to deal with it but to play again. But the hardest thing was just that he wasn't there.

This guy was always right there in front of me...and he wasn't there anymore.

As Gregg told Cameron Crowe in 1973

The real question is not why we’re so popular. I try not to think about that too much. The question is what made the Allman Brothers keep on going.

I’ve had guys come up to me and say, ‘Man, it just doesn’t seem like losing those two fine cats affected you people at all.’

Why? Because I still have my wits about me? Because I can still play? Well that’s the key right there. We’d all have turned into fucking vegetables if you hadn’t been able to get out there and play.

That’s when the success was, Jack. Success was being able to keep your brain inside your head.

You’ve got to consider why anybody wants to become a musician anyway. I played for peace of mind.3

If my notes are right, the 5-man band played 69 shows in 1972, hitting the road pretty hard from late January through August. The grueling tour included the release of the aforementioned Eat a Peach, which hit #4.

The band found solace in the music.

And that’s evident in the latest 5-man band release.

The Tour

The ABB spent much of March in the West, from Vancouver, through California, and across the Great Plains before flying to Puerto Rico in April to headline the Mar y Sol Festival.

From there, they flew to New York. The Syracuse show was the second of 6 shows in the northeast.

They were pretty exhausted.

As TY told me, “They didn’t look happy to be there.”4

The Show

Manley Fieldhouse. Primarily an indoor track and field venue, Manley Fieldhouse had a dirt floor, which they’d cover only for Syracuse basketball games, but not concerts. Thus, the ABB played in a haze of dust in the 6,000 seat arena.

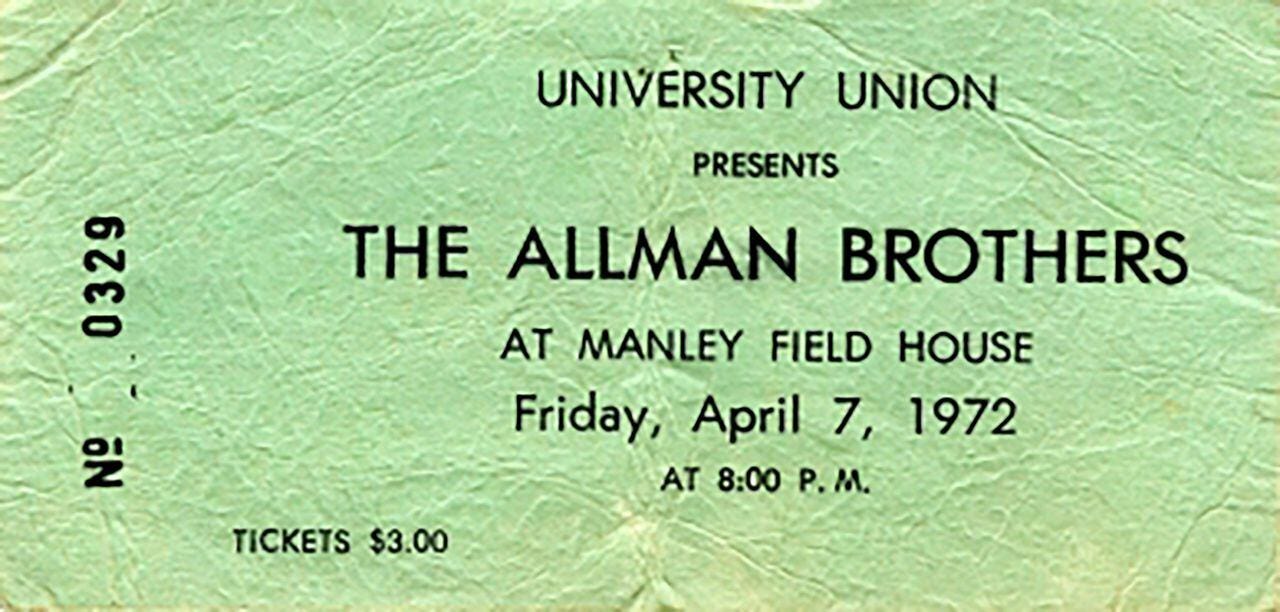

Tickets were $3.

Openers: Dr. John and Wet Willie were scheduled. Wet Willie was a no-show.

The Recording

Jeff Chard not only promoted the show as part of his work as student concert coordinator, he also proposed to Phil Walden an audio simulcast on WAER—FM88 and video to Syracuse’s cable channel.5

Chard is why the show was recorded, and why it survived to be released.

The connection to FM radio is pretty interesting to me.

Those of y’all who lived the era know how groundbreaking FM was compared to AM. I learned in talking to TY that Allman Brothers Band live bootleg recordings circulated throughout the FM radio world. He would regularly play what he had access to, and other DJs did likewise.6

The Setlist

The ABB played 11 songs on 4/7/72.

Seven are from At Fillmore East. They played every song from the album.

Two songs are from Eat a Peach, “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” and “One Way Out” "

“Midnight Rider” is the only song from Idlewild South.

“Syracuse Jam” is the name given for encore jam that segues directly into “Hot' ‘Lanta”

My thoughts

This show has a special place in my heart as the first 5-man band recording I ever traded for. I listened to it a lot…A LOT back in the day. But it’s been years since I’ve really listened to it.

First, no matter how bad things were offstage, playing offered a respite from the grind. Gregg opens the festivities with a benediction:

“We’d like to dedicate the whole concert to each and every one of you all.

And of course, good Brother Duane.”

Then came the formal introduction:

“The best damn band we’re ever gonna hear: the Allman Brothers Band!”

The show starts off somewhat tentatively , particularly in light of what’s to come later in the set.

The group opened with the first two tracks from At Fillmore East: “Statesboro Blues” and “Done Somebody Wrong.”

Gregg counts off, “1, 2—1, 2, 3, 4” and Dickey Betts plays his take on Duane’s familiar “Statesboro Blues” opening riffs. Next is “Done Somebody Wrong”—another turn for Dickey on slide.

In both cases, I feel the band struggling a little bit to get on their feet.

These two songs, more than any other, reflect Duane’s absence in a huge way.

As great as the playing is—and it is—and as hard as they all strive to fill the Duane-sized hole in the songs, “Statesboro” and “DSW” don’t have the same punch to me without a second rhythm instrument.7

“Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” a song near and dear to my heart, follows. And here’s where the group seems to catch their groove. It’s the only song they’ll play this night from Side A of Eat a Peach.8 AWTNM is also the last song Dickey will play slide on the rest of the night.

“One Way Out” is the first of the Duane songs that feels more right. I don’t know how to explain it, but from here forward, the band hits a different groove.

“Stormy Monday” and “You Don’t Love Me” is where the band really catches the wave.

Gregg is particularly strong on both, as a vocalist, accompanist, and soloist.9

Listen to Gregg slowly build his “Stormy Monday” solo as the band segues into Dickey’s solo.

“You Don’t Love Me” follows “Stormy Monday,” and I’m reminded of what a GREAT song it was for the ABB from 1970-1975.10

At Manley Fieldhouse, the band hits a DEEP GROOVE behind Dickey on YDLM about 6 minutes in.

It takes the song in a new direction altogether—Dickey soloing in place of Duane, then taking his usual turn on the rave-up with just the drums behind him.

It’s a fierce, furious take, the band pouring out its pain.

These songs also showcase Dickey and Berry, now the longest musical partnership in the band. Dickey is the sole guitarist and Berry’s lead bass is even more apparent than ever, riding up, under, around, and through the rhythm and soloist.

From YDLM, the band moves into “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.” This is another track where I imagine I’d feel Duane’s absence as I did in the opening two songs.

Don’t get me wrong, all of this music would be better with Duane, but the 5-man band sounded less wrong to me here. Not quite right, because no matter what, the music has a hole in it. What astounds me is how well they fill gap on this run of songs.

Want proof? Listen to Liz Reed from about 8-minutes in.

Gregg introduces “Midnight Rider” as a country song—the first time I ever considered it as such.11

“Midnight Rider” is a respite amidst the fury.

They close the set with a monstrous “Whipping Post.”

And when I say monstrous, I mean…

Monstrous

(Let me try that again…)

MONSTROUS 🍄

The size of the font goes no higher. I would if I could. That’s how BIG it is.

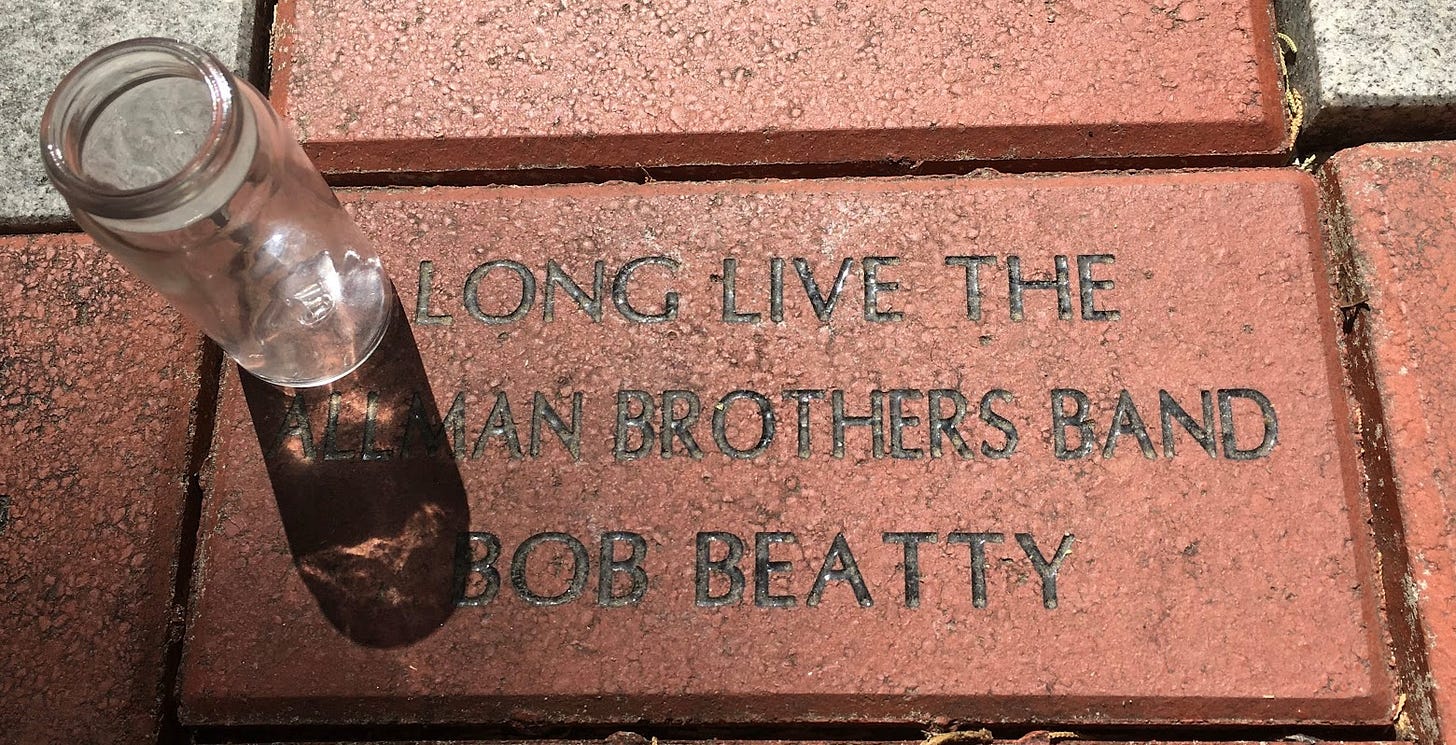

A “Berry Oakley thunderfest”13

From the word go, Berry is pushing and prodding, holding down the bottom end while giving the drummers room to do their thing.

He’s super-sympathetic to his bandmates, particularly under Gregg at the song’s outset.12

Dickey and Berry take over from there.

It’s hardly a surprise that the 5-man band would ABBsolutely DESTROY “Whipping Post,” a song that entered the setlist in spring 1969 for good. Every Allman Brothers Band lineup played it and played it well. Dickey, in particularly, seemed to always conjure some magic on the cut.

The build-up behind Dickey at about 12-minutes in…oh lordy!

As the song draws to a conclusion, Gregg belts out a tribute to Duane, slightly altering his lyrics to:

“There’s no such thing as dying!”

The band returned to the stage for a two-song encore, which is more like an extended jam intro into “Hot ‘Lanta.”

At Manley Fieldhouse, the band gave the same statement they delivered on Eat a Peach. As Gregg said,

“The music hadn’t died with my brother. The music was still good, it was still rich, and it still had that energy. It was still the Allman Brothers.”

Random Notes

The whole Cameron Crowe article is pretty great. The band was really candid with him and his profile was pretty positive. Crowe’s time with them greatly inspired his 2000 movie Almost Famous, including modeling Russell Hammond’s (Billy Crudup) look on circa 1973 Dickey.

Here’s two great sources on the release.

In the “interesting only to me” department, the cover font for this release is the same as on Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East.

At the Brothers show at Madison Square Garden on March 10, 2020 (and again April 16, 2025), Warren used Gregg’s “there ain’t no such thing as dying” line to close the show.13

Drop something in the tip jar to fuel the time, heart, and history behind the work.

Last Sunday morning, the sunshine felt like rain

🍄 This one goes out to Pamela Anne Denney, who was *there* April 7, 1972.

Eat a Peach Video Essay:

Mikal Gilmore, Night Beat: A Shadow History of Rock & Roll (1999).

Cameron Crowe “The Allman Brothers Story: How Gregg Allman Keeps Band Going After Duane’s Death,” Rolling Stone, December 6, 1973.

ICYMI, here’s my full conversation with TY:

This explains to me why some shows are more widely circulated than others. It’s what people taped from the radio.

Speaks to the wisdom of officially adding Chuck Leavell in late 1972.

The three songs without Duane: a helluva statement if you ask me.

Dickey and Berry get a lot of attention for stepping into the breach in 1972, and rightly so. But Gregg’s B3 work stands MIGHTY TALL from my vantage point.

The original band killed it on At Fillmore East, the 5-man band nails it on this set, and the Chuck/Lamar era band’s version on 9/26/73 is the middle piece of some of my favorite 45-min of ABB music of all time.

My first copy of this show was an unlabled cassette. My heart leapt when I heard Gregg’s “country song” intro thinking I was about to hear a 5-man band Blue Sky. (I’m not sure they ever played it as a quintet.)

Another example of Gregg’s stellar B-3 work in 1972.

He did the same at the second of two shows at Madison Square Garden April 16, 2025. (More to come.)

Saw them live later in 1972 (July or August) at Gaelic Park in Bronx, NYC. The show ended with Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, and Bill Kreutzman joining them for the MOUNTAIN JAM encore. Amazing guitar interplay.

July 17th upon research.

The Allman Brothers Band /w Guests, Gaelic Park, Bronx, NYC, 07-1…

www.youtube.com/watch?v=CECo9lhv5fI

www.youtube.com/watch?v=CECo9lhv5fI