I was with the band when it wasn’t no band

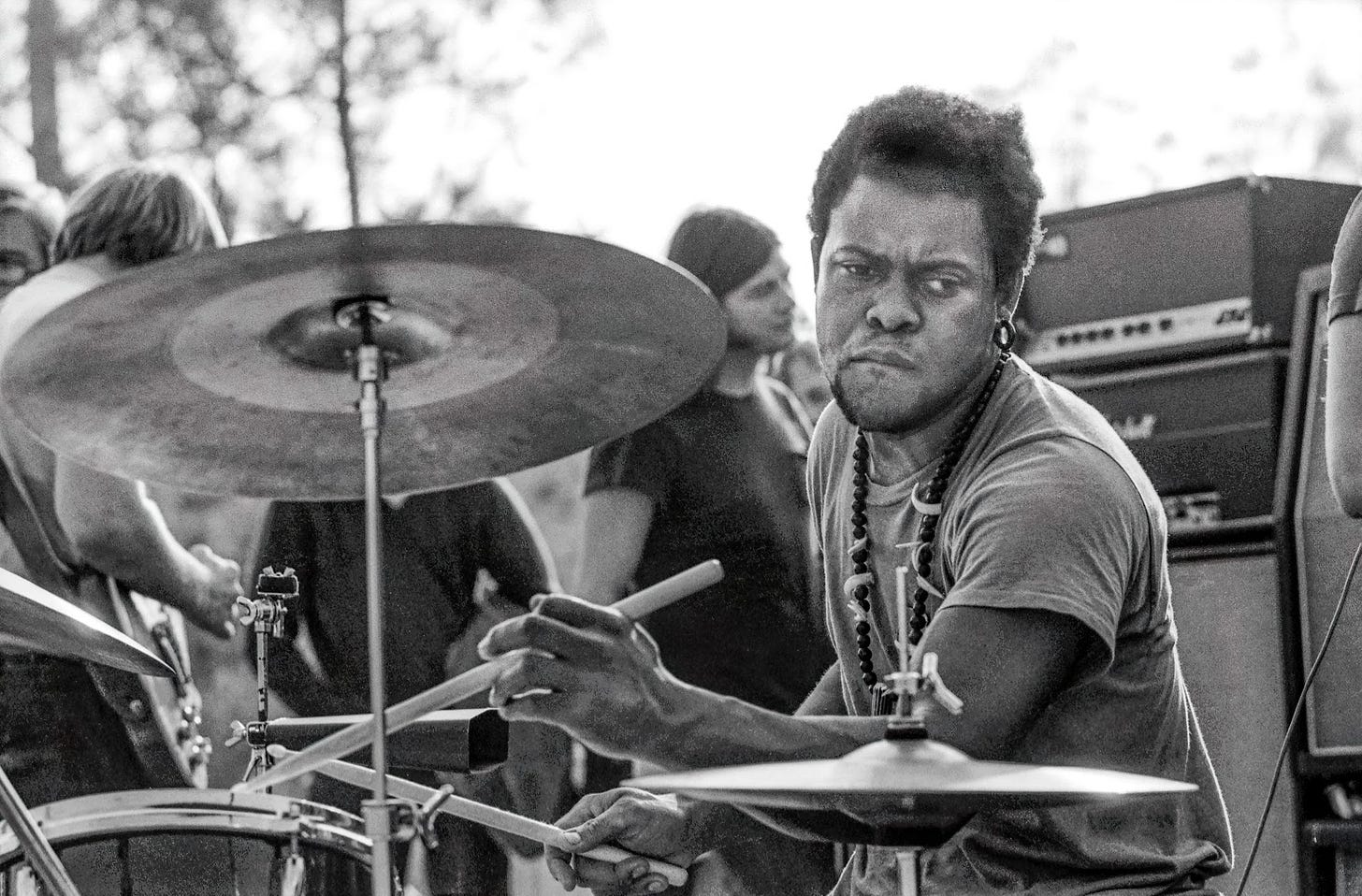

An excerpt from Play All Night on ABB employee #1: Jaimoe

Sending this out, as I do every year for Jaimoe’s birthday. If you’re a longtime subscriber, you’ve encountered it before.

July 8, 2025 is the 81st birthday of the great Jai Johanny Johanson. Duane’s first recruit.

“Was I in the original band?”

“Shit, I was with the band when it wasn’t no band.”

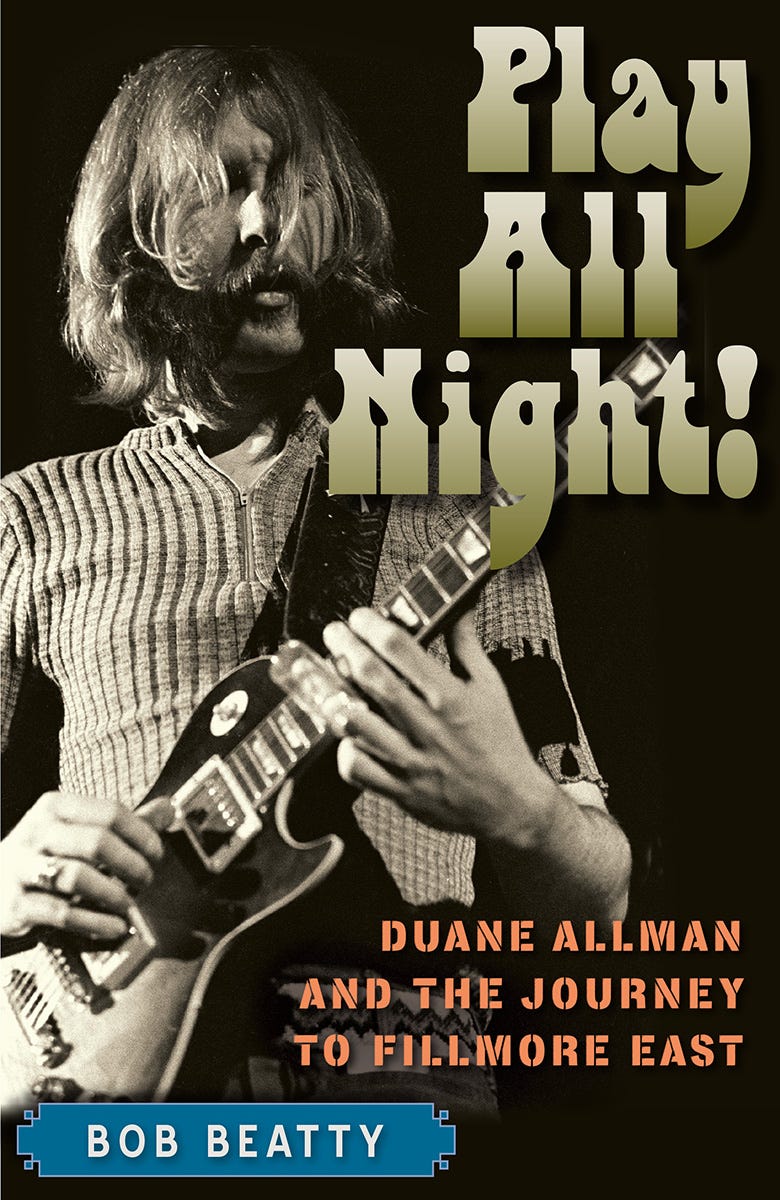

In Jaimoe’s honor, I offer an excerpt from Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East.

Born Johnny Lee Johnson, stage name Jai Johanny Johanson, Jaimoe launched his career from Ocean Springs, Mississippi.

“I didn’t choose music—music chose me.”

Watching pianist Arthur Rubinstein on the Hallmark Hall of Fame television program in the 1950s, he announced to his mother, Helen: “I’m going to play Carnegie Hall.” She “Baby, mother would be proud if you do,” she replied.1

Jazz

Jaimoe found marching band liberating, and drums have consumed his life ever since. His passion for drums coincided with his lifelong love affair with jazz.

“Jazz just slapped me in the face,” he said. “It knocked the sense right out of me.”

He found divine intervention at his school library. “God sent DownBeat magazine to 33rd Avenue High School for me,” he said. “I read that magazine from front to back, everything in it.”

He ignored popular music altogether. “If it wasn’t Miles Davis or John Coltrane, I didn’t want to hear nothing about it.” On short-wave radio and from stations from as far away as Cuba and Europe, he took notes from the percussion players in the big bands of Dizzy Gillespie and Stan Kenton.

His first professional gigs were in 1964 with the Sounds of Soul, a group that included future ABB bassist Lamar Williams.

In 1965, Jaimoe toured with R&B singer Ted Taylor. In April 1966, he joined Otis Redding where his playing fit poorly with Redding’s rhythm and blues.

“I wasn’t ready yet…. I could play my drums and all that stuff, but my timing wasn’t all that good.”

Because jazz is improvised, players need to be adept at staying in the moment while simultaneously anticipating where the music is headed.

Jaimoe had yet to integrate the two poles.

“My timing was terrible because I was always so into the future,” he said. “I wasn’t into what was happening now.”

Jaimoe was an improviser and Redding’s sound depended on a precise rhythm and blues backbeat.

“Otis was into that rock ’n’ roll type thing,” he recalled. “I’m talking about energy. I didn’t have the experience playing like that.”

Plus, “it was way too loud. And I couldn’t play rock ’n’ roll like I can now.”

He left Redding in September 1966 and joined Percy Sledge, where he met Twiggs Lyndon, Sledge’s tour manager. The drummer and Lyndon maintained a regular correspondence for the next two years, leading to Jaimoe’s relocation to Macon in late 1968.

Making music sound good

Jaimoe’s time on the road honed in him a keen understanding of how to best support his bandmates and propel the music forward. In this construct, drums do more than just provide a rhythmic foundation; the drummer helps stitch the music together.

“When I started off I wanted to be the greatest drummer in the world,” he recalled.

“On the road I learned that making the music sound good was more important than my personal gains.”

By 1968 he had grown weary of the R&B touring circuit. “I was done with that whole scene where the people who became stars treated their musicians just like they were treated—like dogs,” he said. “They made all the money, we got all the crumbs.” Even worse, he said, the artists “were so knocked out by what’s going on, they forget what the hell is going on.”

Macon

Life as a backing musician was drudgery. Touring itineraries were demanding. Racism was omnipresent. Pay was abysmal. Things came to a head for in winter 1968 when Clarence Carter’s manager docked him $25 for “driving costs.” When he learned the poorly paying gig didn’t even cover transportation, Jaimoe quit R&B touring permanently.

He had joined Carter’s touring band from Macon. He had relocated there at Twiggs Lyndon’s invitation to play in a studio band Phil Walden was assembling. Jaimoe had even offered to pay his own way to the audition.

“Dig man about that studio gig,” he wrote Lyndon in April 1968, “I am very grateful for your consideration toward me but as I told you on the phone, I’ve surpassed what I was doing and to prove it I will gladly pay back anybody who wants me to audition for them.”

Jaimoe was the first and, as it turns out, the only, musician to sign with Walden’s new rhythm section. Broke and with no discernible prospects ahead of him, Jai resolved to leave the South for New York in pursuit of jazz.

“I figured if I was going to starve to death, it might as well be doing something I love,” he said.

An invitation to join Duane Allman changed his life2

Jaimoe’s initial motivation to meet Duane was mercenary.

“If you want to make some money,” his mentor, drummer Charles “Honeyboy” Otis said, “go play with them white boys.”

“I went down to Muscle Shoals to make money.”

He and Duane found immediate connection from note one.

The partnership centered on one thing:

“The greatest music I ever played.

I knew this was it. I wasn’t going anywhere without him. Two days after meeting Duane, all of my dreams came true.

We didn’t have a nickel but we were all just as happy as could be, doing exactly what we wanted to do.”

Duane’s playing, spirit, and vision matched Jaimoe’s own

Most drummers on the R&B circuit stuck closely to 4/4 rhythms with a heavily accented backbeat, the precision allowing the stars of the show to shine the brightest. Jaimoe was different. Bruce Hampton recalled “richness in his playing” that echoed Elvin Jones and Zigaboo Modeliste of the Meters.

“I had been preparing to play in this band without really knowing what I was preparing for,” he recalled. “It was from playing with all those other musicians that I got all that fiery stuff that people hear in my playing.”

“He plays so weird nobody knows if he’s any good or not,” Phil Walden said to Duane.

“You’re kidding,” said Duane. “This cat’s burnin!”

This cat’s burnin’

What made Jaimoe special was not only that he approached the instrument as a jazz drummer but how great he and Duane sounded together.

While backing R&B stars, the drummer said, he played “bebop stuff on my bass drum, rather than playing a steady pattern that kind of floats along with what the bass player is doing. If you listen to jazz players, they don’t necessarily play the bass drum along with the bass player. They just punctuate here and there, and just do different things with it.”3

Jaimoe’s technique translated brilliantly with Duane, who found his first official bandmate.

“After we started rehearsing, things just sounded so good and loud,” Jaimoe recalled.

“I forgot all about the star trip.”

Jaimoe on Play All Night!

I know I’ve shared this before, but I can’t resist sharing it again. Because honestly, this validation right here is the most important I have had since writing Play All Night.4

Lagniappes: Jaimoe in action

I’ve posted video (and a playlist) below of the following:

Sea Level “Hot ‘Lanta” 2/11/77 Capitol Theatre

Allman Brothers Band “Whipping Post” 9/23/70 Fillmore East (upgraded video)

Jaimoe’s Jasssz Band “Dilemma” 9/14/16

Big Band of Brothers “Don’t Keep Me Wonderin’” 1/27/23 (with Oteil Burbridge)

Friends of the Brothers “Revival” 10/25/24

The Br🍎thers “Black Hearted Woman” 4/15/258 Madison Square Garden5