The Allman Brothers Band's improvisational approach

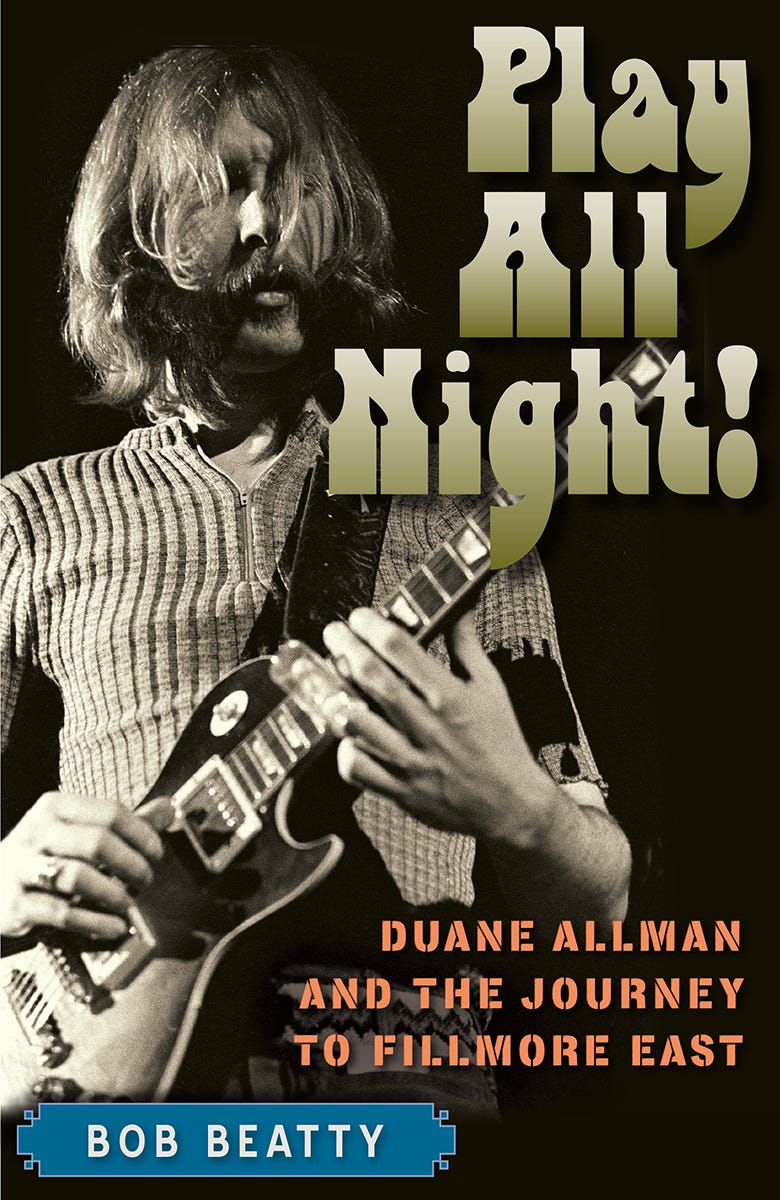

Greetings and welcome back to Conversation from the Crossroads. Today’s essay derives from a virtual book talk for Play All Night,1 moderated by a former student who asked me some fantastic questions.

I had a lot of room to expand on concepts I’d written about in Play All Night and explore the story in other ways.2

This question focuses on a hallmark of the Allman Brothers Band: Improvisation

You point out in Play All Night that Duane and the ABB broke the band mold by performing in a heavily improvisational style, why was this so revolutionary? What was happening in the music industry, in America and abroad, that made this such a change?

This is my improvised response (with edits in post to make it more readable).

First, this is the Woodstock generation. The youth counterculture3 is in full force.

Rock & roll has been popular for more than a decade. By the mid-60s, some blues/blues-rock bands started stretching out in live performance.

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s “East-West” might be the earliest to gain notoriety for it. Cream, Led Zeppelin,4 and Fleetwood Mac with Peter Green followed.

That’s three British blues bands, by the way. Remember it’s the British Invasion that reintroduced the blues to the American public.

(The Allman Brothers and their contemporaries discovered it on their own, on WLAC out of Nashville.)

The British introduced the approach, but San Francisco bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Quicksilver Messenger Service made it their own.

Jamming.

Stretching songs out in front of audiences.

Improvisation was an important part of the experience.

“Momentary composition,” I once heard Warren Haynes call it.

Creating music moment-by-moment.

Performing live made the music spiritual and communal.

That was the Allman Brothers Band’s approach

Here’s Butch:

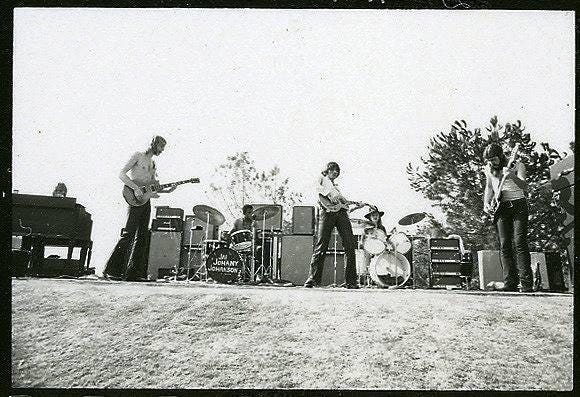

“We got together in Jacksonville and started jamming. Just experimenting, going in all these directions, just stretching the limits of what we'd learned.

We got together the best players we could find in the area, people that could get out and stretch the limits a bit. We started having fun with it.

It's just something that happened.

The whole history of the band and what we stand for I guess is spontaneous. It's been very spontaneous since the very beginning.”5

From jams and improvisations the band developed songs and arrangements.

“Gregg would have a song with chords,” Betts said. “We’d forget about the song and just play off two or three chords, and just let things kind of happen. Berry would start a riff, and everybody would go to that and try to build on it. And if it didn’t happen, we’d go on to something else. As vague as it sounds, that’s why it sounded so natural; that whole thing was a real natural process.”

Jams didn’t only allow the band to get their rocks off, they were yet another way to turn its back on the music business.

“We didn’t want to just play three minutes and it be over,” Gregg recalled. “We were going to do our own tunes, which at first meant mine, or else we’re going to take old blues songs like ‘Trouble No More’ and totally refurbish them to our tastes.”6

Like the Grateful Dead, their exemplars and musical brothers from San Francisco, the ABB shared a philosophy, Dickey said of “keeping music honest and fun and trying to make it a transcendental experience for the audience.”

Where the bands differed?

“We don’t wait for it to happen; we make it happen.”

Jamming with intentionality

The Allman Brothers Band amalgamated a variety of sources into their musical stew, but it’s jazz that sets them apart.

The ABB played with what Ralph Ellison called the “jazz impulse”—“a constant process of redefinition.” The jazz impulse gave artists freedom. Writes Craig Werner, “Who you are, the people you live with and for, the culture you bear, everything remains open to question, probing, reevaluation.”7

In Play All Night, I used one of Duane’s most cited influences, John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” as an example of the jazz impulse in action.

Coltrane expands the Rodgers and Hammerstein show tune to thirteen-plus minutes, with the saxophonist and pianist McCoy Tyner improvising solos over a two-chord vamp.

Each begins with an interpretation of the melody, providing a familiar frame for listeners. After soloing for several measures, the saxophonist and pianist return to the melody, signaling a transition to the next section of the song for bandmates while also offering a change of pace for the listener.

At the end of Coltrane’s second solo, he plays the melody one last time, the coda completing the passages Coltrane began nearly twelve minutes earlier.

With “My Favorite Things,” Coltrane completely changed a two-minute show tune into one of the best-known jazz tracks in history.

So you have the basis of the song, you have markers along the way for where you go—movements in the song, changes, etc., and everything else is up to the players.

Listen to the extended jams on At Fillmore East—“You Don’t Love Me” “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” “Whipping Post”—and you’ll hear these same guideposts.8

The live experience adds an additional degree of difficulty. Playing live, you’re feeling energy from your bandmates, from the crowd. You could have smoke in your eyes because you’ve got a cigarette in your mouth. You could be looking at somebody in the audience who’s yawning or someone who’s digging the shit out of it.

Listening is where the ABB excelled

With so much going on, a structured song with long instrumental passages, soloists at liberty to go wherever the muse took them, playing live, they had to be good listeners just to keep up.

But even more than that, they responded to each other in those moments, something you can hear clearly on At Fillmore East.9

Listen to the band behind Duane and Dickey. Hear how Jaimoe and Butch respond to the soloists, or how Berry and Gregg are all tying it all together with the bass and that heaping scoop of B3 gravy.

At Fillmore East took the improvisational live approach of their generation to another level. Up to that point, jam-heavy, improvisational, live records were the purview of jazz.

That the record hit #13 was proof positive that the Allman Brothers Band formula worked commercially.

They captured on tape four sets, all ABBsolutely stellar, two nearly flawless, and curated a groundbreaking record out of it.

With zero overdubs.

Yep, zero overdubs

This might be the most astounding part of it all. They made some edits in post, but the album At Fillmore East is 100% live.10

They recorded their make-or-break third album on the most important stage in rock.

They walked the highwire composing in the moment in front of a couple thousand people.

And they didn’t change a note in post.

Talk about hittin’ the note.

Supporting Conversation from the Crossroads

This entire endeavor is my effort to discuss about the South and its influence on American history. I’m using skills honed in history museums and sites and with and for communities to look at these intersections from one specific lens: the Allman Brothers Band.

It’s more than just Substack posts.

It’s interviews for Play All Night on Youtube, short-form content on TikTok, digital shorts on Instagram, and daily posts on Facebook and all of the above.

I am reaching folks where they are, providing a lot of material across social media—more than 50,000 followers across all platforms. That’s the “public” part of my historian’s hat.

My main focus has always been here on Substack.

Substack is where I expand my ideas into longer essays that address my thoughts from the crossroads of Southern music, history, and culture. In less than two years, this account has grown to more than 4,000 subscribers.

Paid subscriptions underwrite the cost for me to bring all of this conversation forward. I figure I’m offering at least $2.50 in value a week to you here on Substack, but you may be finding me elsewhere. I am grateful for each of you, who finds value in supporting what I’m doing.

Some readers have reached out to support my work without springing for a full Substack subscription. Here are three ways to throw a tip in the jar:

🍄 VENMO

🍄 PAYPAL

🍄 CA$H

And no matter what, I really appreciate each of you for being here and for engaging.

Thanks for reading y’all.

Here’s the first essay in the series, Duane Allman’s Leadership.

The Unending Conversation in action.

The Baby Boom generation, btw.

Both led by former Yardbirds guitarists: Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page.

Play All Night, 106-7.

Play All Night, 105-7.

They’re there in all the songs, but it’s most prominent in these three.

It’s been awhile since I lauded Tom Dowd’s stellar production on this album, including the way he mic’d the room. The room sounds *alive*.

Specifics here: At Fillmore East as an Artistic Statement.

Great essay. Particularly like making explicit the Coltrane connection. I’ve often thought about kind of passively, more as a leap of faith. Now the connection is clear.

Improvisation is a forgotten talent in the modern industry. Its so cool to see bands, like Allman bothers in years prior, really take on the most pure form of musical expression with improvised live jams at their shows.