Maybe the only thing that saved us was everybody was scared of us

The Allman Brothers Band relocates to Macon

Welcome back to Long Live the ABB: Conversation from the Crossroads of Southern music, history, and culture. Glad to have you here.

Today’s post focuses on the first 5 (or so) months of the Allman Brothers Band, from their founding in Jacksonville, moving to Macon and meeting Mama Louise, through the recording of their debut album in August 3-12 at Atlantic studios, NYC.

What I’m Reading/Watching

Sticking just to to music-related books (for now).

Daniel De Visé The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic (2024). I’m a big fan of the movie from way back—and this was a fun read for sure.

More importantly, it led me to…

Daniel De Visé King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of B.B. King (2021). The book is a terrific, thorough biography of the King of the Blues, and a key influence in not only Duane and Dickey, but also Warren, Jack, and Derek.

Warren Zanes Petty: The Biography (2015). I skimmed this when it first came out, paying attention to Allman Brothers references mostly. My second read proved more fulfilling. I’ve always felt a connection to Tom Petty because of our shared Florida roots.

Which led me to…

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers: Runnin' Down a Dream (2007), a 4+ hour documentary. Well worth the watch. If only for Tom singing “Southern Accents” in his hometown of Gainesville.

Part 7 of my annotated read of the Allman Brothers Band: A Biography.

Here’s parts 1-6 Marginalia series1

I’ve posted the full book here

Today I’m highlighting Just four paragraphs.

Marginalia

The original text looks like this.

The marginalia looks like this.

Previously on Long Live the ABB…

“Jesus Christ! What a band!” Gregg Allman

Gregg:

“It was such a pleasure playing and singing with them. They had never heard any vocal over their music, in the three months they’d been together.

Duane had planned it that way; he was getting the whole band so it would be already a little rehearsed by the time he called me.

I felt so good about everything, in the next week or so I wrote ‘Whipping Post,’ ‘Blackhearted Woman,’ and ‘Every Hungry Woman” and I wrote on the average a couple songs a week, from then on.”

It wasn’t three months, probably wasn’t even 3 weeks total. But yeah, they’d never heard vocals like Gregg’s before. He was just what the band needed.

Don’t miss Gregg’s observation that that’s exactly how Duane planned it. He pulled the band together, worked it out a bit, and called Gregg to “round it up and send it somewhere.” The band lived on for 45 years.

Here’s where the book picks back up.

Macon

The band practiced in Butch Trucks’ house, as well as at a Jacksonville club called the Beachcomber, until frequent trips to Macon for replenishment of funds—Phil Walden was their sole source of income—made moving to Georgia a logical step.

Nolan places both the jam that founded the Allman Brothers Band 3/23/69 and subsequent rehearsals at Butch’s house. As far as I know, those jams all happened at the Gray House at 2844 Riverside Avenue in Jacksonville.2

As the Allman Joys, Duane and Gregg had played the Beachcomber Lounge with Butch Trucks sitting in on drums. Duane scored Butch’s band, the Bitter Ind,3 an audition, which they parlayed into a months-long stint in the club.

The Beachcomber is where Berry’s future wife Linda first met Duane and Gregg. A year or so later, she is who introduced Berry and Duane.

Walden funded their early days, but the reason they left Jacksonville for Macon was legal trouble, specifically a gun charge for Dickey.4

Twiggs ensconced them in his old apartment at 309 College Street, in two rooms covered with wall-to-wall mattresses. There was also a Coke machine filled with Budweiser.

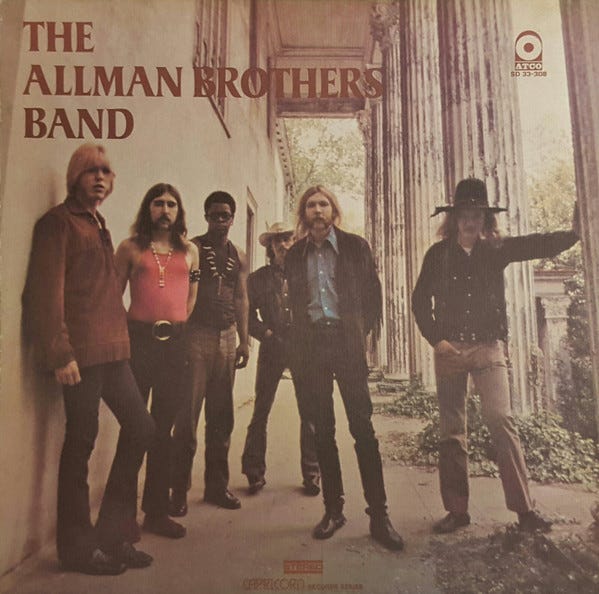

That apartment, at 309 College Avenue in Macon, was the infamous Hippie Crash Pad. It was only in the last decade I realized it was right next door to the site of the first album cover photo shoot.5

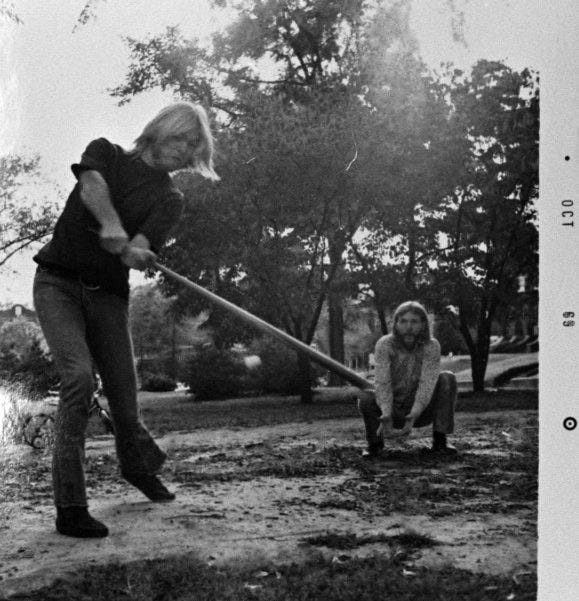

Butch Trucks says, “We used to come in after practicing all night, take some psilocybin, and start playing corkball6 in the apartment. Four, five in the morning—screaming, hollering, sliding into the Coke machine (that was third base).

Instead of calling the cops or anything, everybody in the apartment building just moved out. When we finally got evicted from that place, we were the last ones left.

And I mean, we were a perfect bust.7

In Macon, at that time, nobody had even seen any long hair. Maybe the only thing that saved us was, everybody was scared of us.

They didn’t know what we’d do! I’m really surprised we got away with all that. Macon’s been good to us in ways like that.”

Marginalia reserved for paid subscribers of Long Live ABB

The long hair was an ABBsolute anomaly. People used to drive by the Hippie Crash Pad to gawk at the newly arrived hippies.

In addition, as Mama Louise Hudson proprietor of the H&H (more below) reported, “Macon was just barely integrated. Nobody around here had seen guys who looked like them. I had not. A lot of white folk around here did not approve of them long-haired boys, or of them always having a black guy with them.”

Twiggs’s brother A. J. recalled a visit to the Hippie Crash Pad. “I remember seeing a little blonde head on Jaimoe’s chest and thinking, ‘Well, this is different.’”

The arrangement was indeed different, but Macon seemed to accept the band with few hassles. “We were a little apprehensive about going to a real small Southern town. We were some pretty off-the-wall characters,” Betts said. The band kept its focus on music and somehow earned a “pass” from the Macon community. “People realized we were there for the music,” said Dickey.8

In Macon, the band practiced at Walden’s newly-opened Capricorn Recording Studios, and at a warehouse named the Hammond Building, for three or four months prior to recording their first album, playing only one gig by Butch’s recollection, at Macon’s College Discotheque.

“This Top 40 disc jockey came out after we were through and said, Well, I don’t know if that was good, but it sure was loud.’” Twiggs remembers that date too: “We had 37 people at a dollar a head. We took the money and bought $7 worth of food and $30 worth of Ripple.”

A quite inauspicious beginning, don’tcha think?

I wrote about the band’s first Macon gig here: An Experimental Blues Rock Music Feast

The Allmans’ daily regimen during this time included regular meals at the H&H Restaurant, whose proprietress, Mama Louise, extended weekly credit to the group.9

Twiggs theorizes her down-home cooking did more than merely keep the band alive during those first lean months:

“It’s my feeling her food affected the music. It’s so good, that you eat ‘fill you’re about to pop; then it puts you in a certain laidback disposition until it’s digested. It weighs upon you heavily. If you have six musicians, who get up at ten, eleven in the morning and all go down and eat the same type of food at the same time—they’re all automatically put on the same physiological note. You know what I’m saying?

If they went then from her restaurant to the studio and began to play, while the food was starting to digest among the six of ‘em—I think you can get a lot more done with six people in the same frame of mind, than if one guy’s still half-asleep, and another one’s got a whole lot of energy; you don’t have the same meld, then. That may be my imagination, but I like to credit Mama Louise for some of the good things that happened on those first albums.”

The H&H was just down the street from Phil Walden’s office on Cotton Avenue.10 As story goes, three or four of the band/crew visited one afternoon and ordered a single plate of food. When Mama Louise saw they were all eating off that one plate, she emerged with a plate of food for each one of them. (For the cost of only one, I imagine.)

She also served them on credit in their early days, allowing them to return and pay their tabs after a tour run had earned them a little money. Things were certainly lean for the band, their only steady income was from Red Dog and Twigg Lyndon’s military benefits. Said Butch, “We learned how to buy cigarettes and wine and food for three dollars a day. And that's how we lived for about two years.”11

And there’s something to be said for Twiggs’s take on how connected the Allman Brothers Band were to each other in the early days. It comes out in the music for sure.

Although their first two albums lack the fire, cohesive vision and conviction of all their later work, it is possible in retrospect to see in them the seeds of what the ABB would become.

If I were to post this out of context on social media, some people would go apeshit because they disagree with the assertion that anything could be “wrong” about something Duane did.12

And to my ear,13 neither The Allman Brothers Band nor Idlewild South lack “fire” “cohesive vision” nor (most assuredly) conviction(?!). If anything comes through from listening to the Allman Brothers Band, it’s that they mean what they’re playing, particularly in this era.

But the latter part of this sentence is really the point he’s making—Those albums are good and all, but two years later they’d release a masterpiece.

Methinks that’s a pretty fair take.

The opening chords of “Don’t Want You No More” (which segues into “Not My Cross to Bear”) on The Allman Brothers Band are dramatic enough to announce the arrival of an ambitious group of musicians with some sense of where they’re headed; but the track seems to lose momentum as Gregg’s subdued organ becomes prominent.

Dramatically announce the band’s arrival is an understatement. The opening five notes of “DWYNM” are an emphatic beginning.

And I don’t know about you, but ain’t no “lose momentum” about anything happening in the first two tracks of the Allman Brothers Band’s debut. “Cross to Bear” just flows right out of “DWYNM”—with Gregg’s organ right where it needs to be.

The rest of the album continues to alternate between passages of power—a “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” type field chant on “Black Hearted Woman;” the thoroughly realized “Trouble No More,” with strong dual lead guitars, a striking ensemble line and a commanding Gregg Allman vocal—and tentative moments that reflect the band’s newborn status.

“Trouble No More” is the first song the group worked up together.

Listen closely to the studio version from the debut album for Duane playing rhythm on acoustic guitar.

I’m 99% sure Duane’s playing slide in standard tuning here, as John Hammond didn’t show him open E tuning until later in the year.

Anyone expecting to hear “Duane Allman & Co.” was quickly divested of that misapprehension; Duane’s spare, meditative solo on “Dreams I’II Never See” stands out on an album where individual work is for the main sublimated in a group effort. “Whipping Post” ends the album on an affirmative plane and hints at things to come.

This is a very “live-sounding” album, recorded in one week’s time, and the production by Adrian Barber seems not to have been especially suited to a group whose debut might have been given a bit more polish. Still, it served to get that “first album” out of the way, and, raw as it is, there’s nothing to be ashamed of on The Allman Brothers Band.

No one was ever happy with the production or sound of the first album. “We didn’t spend enough time on it,” Gregg said. “We didn’t refine it enough. We were better than that.”

And Nolan’s right about all of this: the band was a BAND. Only on “Dreams” did Duane stand out from the group. “Whipping Post” was a fitting end to the record, as it would be two years later, and nearly 18 minutes longer, on At Fillmore East. His observations stand the test of time.

Up next in this series…

Touring in the early days.

There’s a historical marker there, the first Allman Brothers Band-related historical marker in Florida that I know of. Derek Trucks unveils historical marker.

For “Individual” (killer wordplay).

Here’s a KILLER Charlie Pierce piece on corkball, “The Sport That Time Forgot.”

This was only months after they’d been busted in Jacksonville!

Adapted from Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East, p132.

Here’s me riffing on Mama Louise

Same general area as today, but a different location—in an old filling station actually.

Scott Freeman, Midnight Riders: The Story of the Allman Brothers Band (1995), 48.

This is not hyperbole. Way too many people take personal offense on social media about opinions they disagree with—often slandering the source as unreliable at best, worthy of physical harm at worst. (That is also not hyperbole. This has happened on my Long Live the ABB Facebook page more than once.)

I’m deaf in my right ear since birth.